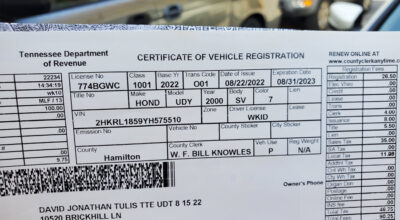

Victim of a state fraud, Quintrise Michelle Branham is led away by Chattanooga police officers on a warrant for failure to appear. She had a driver license suspended, though she had not applied for such license and is among the working poor bedeviled by police enforcement of commercial traffic law in Title 55 of the Tennessee code. (Photo Chattanooga police department)

A lawsuit filed against Tennessee in federal court in Nashville to prevent senseless and harsh consequences of commercial government upon the poor is overturned in the court of appeals in Cincinnati in a 2020 ruling. A concurrent opinion by Ransey Guy Cole Jr. outlines the case and expresses regret that results cannot be different. Robinson v. Long, 814 F. App’x 991. He served as chief judge from 2014 to 2021 and assumed senior status Jan. 9.

The case filed by three poor people whose driver licenses are revoked attempts to solve half the problem created by converting the right of ingress and egress (aka travel) into a commercial activity. That is that movement, even if under state auspices of “driving” or “operating” a “motor vehicle” is essentially a fundamental right.

Lawyers who filed the case fail to make the distinction between travel and transportation. The first is a right. The second a privilege. While ignoring this distinction, the U.S. district court in Nashville rules justly the state’s revocation policies against the poor is irrational, punitive and partial against poor people. The controlling presumption is that without a driver license, they must stay at their houses and not use the roads in any way by car. If their licenses are revoked, they use the roads under threat of criminal sanction. Often, the necessity of using the roads brings these poor people new criminal charges, new oppressions, jailings, court cases, sentences and harm.

The petition for injunction fails to separate true private users and assert their fundamental rights under the constitution to move under land right of ingress or egress or the constitutional guarantees of occupation, religion, communication and other rights enjoyed in the context of movement by automobile.

Still, the lower rulings by Aleta Trauger contain many statements serviceable to my demand for an end to commercial government oppression against the people in Tennessee and their right of movement and communication.

‘Trying to squeeze blood from a stone. Nothing will come but pain’

I concur in judgment in light of the fact that Fowler v. Benson, 924 F.3d 247 (6th Cir. 2019), is binding precedent in this circuit. Because I believe that Fowler was wrongly decided, I write separately to note that if we were not constrained by Fowler, I would affirm the district court’s order granting a preliminary injunction.

6th circuit court judge Ransey Guy Cole Jr.

By Judge Ransey Guy Cole Jr. / 6th circuit court of appeals

Even under rational basis review, the challenged law is unconstitutional as applied to the certified plaintiff class, which consists only of Tennessee residents “who cannot now and could not at the time of [their license] suspension afford to pay *996 [their traffic] debt.” (Dist. Ct. Op. re Class Cert., R. 151, PageID 2311, 2403.)

Taking away residents’ driver’s licenses as punishment for their poverty furthers no legitimate government interest. It actively impedes the ability of the state to collect, as it hinders the ability of residents to earn money to pay their debt. See, e.g., Tate v. Short, 401 U.S. 395, 399, 91 S.Ct. 668, 28 L.Ed.2d 130 (1971) (finding that imprisoning drivers too poor to pay traffic fines, while ostensibly “imposed to augment the State’s revenues,” “obviously” impedes that purpose rather than serving it). The idea that license suspension will encourage indigent residents to pay their traffic debt is irrational. See Fowler, 924 F.3d at 272 (Donald, J., dissenting) (“It is difficult to rationalize … how suspending the driver’s license of a person who is truly unable to pay makes it any more likely that [the state] will recover the costs it seeks to collect.”); see also, e.g., Bearden v. Georgia, 461 U.S. 660, 670, 103 S.Ct. 2064, 76 L.Ed.2d 221 (1983) (“Revoking the probation of someone who through no fault of his own is unable to make restitution will not make restitution suddenly forthcoming.”). Attempting to incentivize impoverished Tennessee residents to pay traffic debt by suspending their licenses is like trying to squeeze blood from a stone. Nothing will come but pain.

It is no answer to say that the presently impoverished plaintiffs may, at some unknown future time, come into money, and the current suspension of their driver’s licenses will incentivize them, at that time, to pay this debt before all others. Cf. Fowler, 924 F.3d at 263. From the moment the plaintiffs’ driver’s licenses are taken away until that hypothetical, future time when they acquire excess funds, their constitutional rights are violated by the state’s withholding of a vital property interest on the sole basis that they are too poor to pay. See, e.g., Cleveland v. United States, 531 U.S. 12, 25 n.4, 121 S.Ct. 365, 148 L.Ed.2d 221 (2000) (explaining that “individuals have constitutionally protected property interests in state-issued [driver’s] licenses”) (citing Bell v. Burson, 402 U.S. 535, 539, 91 S.Ct. 1586, 29 L.Ed.2d 90 (1971)); Bearden, 461 U.S. at 671, 103 S.Ct. 2064 (rejecting the notion that a state can “punish[ ] a person for his poverty”). While the plaintiffs remain indigent, offering them the opportunity to pay a fine or have their license taken away is an “illusory choice,” as an “indigent [person], by definition, is without funds.” Williams v. Illinois, 399 U.S. 235, 242, 90 S.Ct. 2018, 26 L.Ed.2d 586 (1970).

Nor is it an answer to say that the suspension of the plaintiffs’ licenses furthers the state’s interest in compliance with traffic laws. Cf. Fowler, 924 F.3d at 262. Other Tennessee residents, who violated those same traffic laws, were able to keep their driver’s licenses upon payment of a fine. The only difference between those residents and the plaintiffs is that the plaintiffs are too impoverished to pay. A state cannot impose a harsher punishment on one resident than another for the same offense on the sole basis that one is unable to pay a fine. See Williams, 399 U.S. at 242, 90 S.Ct. 2018; Tate, 401 U.S. at 399, 91 S.Ct. 668. Just as “the ability to pay costs … bears no rational relationship to a [criminal] defendant’s guilt or innocence,” the ability to pay fines bears no rational relationship to a resident’s fitness to drive. See Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12, 17–18, 76 S.Ct. 585, 100 L.Ed. 891 (1956) (plurality).

By vacating the district court’s preliminary injunction, we allow Tennessee to deprive thousands of residents of their only means of obtaining food, accessing medical care, or getting to work. See Bell, 402 U.S. at 539, 91 S.Ct. 1586 (describing driver’s licenses as “essential in the pursuit *997 of a livelihood”). The district court found that for most Tennessee residents, “public transportation … is widely insufficient to provide an adequate substitute for access to private motor vehicle transportation.” (Dist. Ct. Op. re Prelim. Inj., R. 222, PageID 4003–04.) Stripping people of their driver’s licenses because of their inability to pay is not only cruel and unwise; it is unconstitutional. I regret that, until a change comes from the en banc court or the Supreme Court, Fowler forecloses us from rectifying this injustice.

Robinson v. Long, 814 F. App’x 991, 995–97 (6th Cir. 2020)