A circuit court clerk takes my filings demanding immediate injunction against a state-based extortion racket under color of financial responsibility law of 1977. (Photo David Tulis)

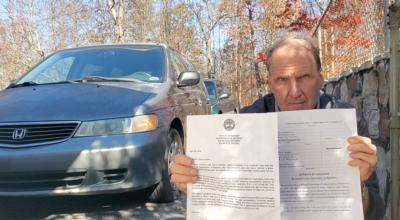

My two cars are revoked by David Gerregano, Tennessee’s commissioner of revenue, under a fraud I am targeting in three lawsuits. My 1999 RAV4 bears a colorful vanity plate asking the cop, “Do you have reasonable articulable suspicion of a crime?” (Photo David Tulis)

I file today my injunction for immediate relief in the public interest, defending my right to use the roads commercially without insurance. (Photo David Tulis on TikTok “smartest guy with a bow tie.”)

Nick Barca, right, an employee lawyer with the Tennessee attorney general’s office, sits in a court in Nashville with two other state lawyers, defending a massive industry-capture fraud in Tennessee under color of financial responsibility. (Photo David Tulis)

CHATTANOOGA, Tenn., Saturday, Oct. 4, 2025 — I am suing to end a mass fraud run by Gov. Bill Lee against the public in Tennessee. My complaint in circuit court of Hamilton County sets forth a petition for judicial review based on two-year litigation record in the department of revenue in a contested case. My complaint, a defense of the black letter law of the Tennessee financial responsibility law of 1977 (“TFRL”) and its Atwood Amendment (“Atwood”), also demands injunctive relief.

I file my motion for injunction Friday with demand for a special master to help restore the department to a reputation of honor, a program of obedience to law and compliance with the norms of honest government service. Petitioner demands immediate relief as a matter of law.

In seeking injunction, I have to show continuing irreparable harm warranting what is called extraordinary relief. This section from my brief makes a defense of what is commonly called “the right to travel” and how this right is continually breached by what I call “The Eye of Sauron” program run by revenue and also by Jeff Long, commissioner of department of safety.

Right of ingress-egress, communication, private purpose

Petitioner also defends a separate body of constitutionally guaranteed rights that respondent continually abrogates. These include freedom of movement, communication, and ingress–egress apart from privilege, alongside due process rights within the privilege system itself.

Loss of use of the 2000 Honda Odyssey minivan injures petitioner daily. He is forced to remain near home, relying on walking or bicycling to communicate person and property, rather than using the people’s roads. This curtails efficiency, time and liberty.

Respondent categorically rejects and denies the distinction between public and private use of the public road and the right of ingress and egress. “Title 55 of the Tennessee Code Annotated does not address or recognize Petitioner’s asserted rights or otherwise indicate that such rights impact the registration of his motor vehicle in any way” (TR p. 522, memorandum in support of summary judgment p. 14), “Claimed Right to Purportedly Private Operation of the Vehicle” (TR p. 1,043, initial order p. 45).

SERVICE COPY – Tulis v. DOR – motion for injunction plus brief,affidavit,draft order

Respondent alleges petitioner has “adjacent claims” described as “a fundamental right to the private operation of his vehicle on Tennessee roads” (TR pp. 1,138, 1,139, deputy Cmsr. Christine Lapps’ final order upon agency review, pp. 14, 15). Claiming petitioner argues for a right to “[operate] his vehicle” apart from licensure, respondent misrepresents his position founded on constitutional guarantees. Respondent uses terms (“drive,” “operate” or “vehicle”) without the factual evidence to the elements of the terms. Petitioner uses the road in his automobile when exercising rights. He operates a vehicle when in privilege Nonrecognition of rights and their abstractification are in bad faith.

DOR intends to humiliate members of the public and subjugate petitioner.

Petitioner has not argued a right to operate a motor vehicle without registration. He has consistently argued that “driving and operating” are privilege taxable activities, while “using an automobile” is a constitutionally protected liberty. Respondent’s refusal to recognize the scope and limits of its authority, and its insistence that all road use is privileged, reveals arbitrary and capricious conduct.

The distinction between use and operating is longstanding in law. Regulation attaches to privilege taxable activity or commerce, not to private use. See Cont’l Baking Co. v. Woodring, 286 U.S. 352, 354–73, 52 S. Ct. 595, 596–602, 76 L. Ed. 1155 (1932), holding that Kansas could impose added burdens on commercial carriers but not compel private carriers to become public carriers. Tennessee, like Kansas, has no authority to force private citizens — whether journalists, grandmothers, or plumbers — into the status of public or private carriers. Driving and operating a motor vehicle is a privilege taxable activity. “‘The state of Kansas has constructed at great expense a system of improved highways. These have been built in part by special benefit districts and in part by a tax on gasoline sold in the state and by license fees exacted of all resident owners of automobiles. These public highways have become the roadbeds of great transportation companies, which are actively and seriously competing with railroads **599 which provide their own roadbeds; they are being used by concerns such as the plaintiffs for the daily delivery of their products to every hamlet and village in the state. The highways are being pounded to pieces by these great trucks which, combining weight with speed, are making the problem of maintenance well-nigh insoluble. The Legislature but voiced the sentiment of the entire state in deciding that those who daily use the highways for commercial purposes should pay an additional tax. Moreover, these powerful and speedy trucks are the menace of the highways.’ It is apparent that Kansas, in framing its legislation to meet these conditions, did not attempt to compel private carriers to become public carriers.” Id. Cont’l Baking Co. (emphases added).

Gov.Bill Lee visits with state troopers who help enforce the fraud of “mandatory auto insurance” in violation of the TN financial responsibility law of 1977 that I defend in court. Top right is David Gerregano, revenue commissioner, and Christine Lapps, deputy commissioner, who inked final department filings in our case, Tulis v. DOR. (Photos department of revenue, governor’s office)

Authority to regulate privilege does not stand for the proposition that all use of the road is privileged or subject to privilege administration or is prohibited if apart from privilege.

“We are of opinion that there is no ambiguity about the ordinary meaning of the expression ‘public highway.’ We think there can be no doubt that the common understanding of a public highway is such a passageway as any and all members of the public have an absolute right to use as distinguished from a permissive privilege of using same”

Standard Life Ins. Co. v. Hughes, 203 Tenn. 636, 642, 315 S.W.2d 239 (1958) (emphasis added).

Law enforcement officers (“LEO”) statewide following respondent program will use criminal enforcement authority to arrest and criminally charge petitioner for “driving on revoked,” apart from exhaustion of administrative remedies in privilege disputes, even though he may not be driving or operating, but merely using the public road. If a person under privilege is challenged for an act under license (damaged taillight, traveling with a revoked tag, missing taglight), he has a right under privilege to an administrative contested case hearing in department of safety under UAPA. This right to have the state exhaust its administrative remedies under that well-known doctrine is universally ignored. Petitioner faces the certainty of criminal arrest and criminal charges based on the revoked plate and the allegation of “driving and operating.”

The very risk is a harm, a prior restraint of his press and other liberties.

Without injunctive relief, petitioner’s God-given constitutionally guaranteed inalienable rights are abrogated by criminal police power exercise of other parties not under respondent control based on respondent policy of tag revocation and its acts. Petitioner’s enjoyment of his personal rights is not dependent on any grant, license, tax, permit, privilege, favor, benefit or exemption.

The harm of respondent’s program falls across the spectrum of constitutionally secured liberties. It restrains petitioner’s free exercise of religion (Tenn. Const. art. 1 § 3; U.S. Amend. I), his freedom of the press as a working journalist (Tenn. Const. art. 1 § 19), his right of peaceable assembly (Tenn. Const. art. 1 § 23), and his right of access to courts (Tenn. Const. art. 1 § 17). It violates protections against unreasonable searches and seizures and deprivation of liberty or property without due process (Tenn. Const. art. 1 §§ 7–8), and it forces him into unwanted insurance contracts, contrary to the right to contract (Tenn. Const. art. 1 § 21). It diminishes his private property rights reserved under Tenn. Const. art. 2 § 28 and case law such as Phillips v. Lewis (1877), and it denies his statutory right to free use of public roads (T.C.A. § 67-5-204). These interlocking violations confirm that respondent’s program abrogates not one liberty but the whole constitutional framework, and that the resulting harms are irreparable.

CONSTITUTIONAL PARTICULARS

Petitioner rights under the constitution are facing continuing abrogation:

-

- Religious rights. “That all men have a natural and indefeasible right to worship Almighty God according to the dictates of their own conscience[.]” Tenn. Const. Art 1 § 3. Everything petitioner does is for God’s glory, to advance the kingdom of God about which the Lord Jesus Christ talks repeatedly. Petitioner uses his minivan as an automobile for free exercise of religion. He denies any claim this liberty is subject to police power threats originating from a revoked tag. Petitioner refuses under religious conscience to ask permission of anybody for free use of the road by which he accomplishes his ministry and religious purposes. These rights are also protected under U.S. Amend. I.

- Press rights. “That the printing press shall be free to every person to examine the proceedings of the Legislature; or of any branch or officer of the government, and no law shall ever be made to restrain the right thereof.” Tenn. Const. Art 1 § 3. Petitioner’s exercise of press rights is at liberty, apart from any privilege, but respondent for decades has misled law enforcement officers into viewing every member of the public using an automobile as presumptively in commerce.

- Right of assembly. “That the citizens have a right, in a peaceable manner, to assemble together for their common good, to instruct their representatives, and to apply to those invested with the powers of government for redress of grievances, or other proper purposes, by address or remonstrance.” Tenn. Const. art. 1 § 23. Respondent privies will arrest petitioner using the road to attend an assembly.

- Right of access to courts. “That all courts shall be open; and every man, for an injury done him in his lands, goods, person or reputation, shall have remedy by due course of law, and right and justice administered without sale, denial, or delay.” Tenn. Const. art. 1 § 17. Use of the van to conduct business in court will bring arrest and a criminal charge “driving on revoked” in direct consequence of revocation.

- Right to pursue calling of common right. “That the people shall be secure in their persons, houses, papers and possessions, from unreasonable searches and seizures; and that general warrants, whereby an officer may be commanded to search suspected places, without evidence of the fact committed, or to seize any person or persons not named, whose offences are not particularly described and supported by evidence, are dangerous to liberty, and ought not to be granted.” “That no man shall be taken or imprisoned, or disseized of his freehold, liberties or privileges, or outlawed, or exiled, or in any manner destroyed or deprived of his life, liberty or property, but by the judgment of his peers, or the law of the land.” Tenn. Const. arts. 1 §§ 7 and 8). Earning a private living by enjoying rights of ingress and egress from his abode is foundational to liberty, which concept scandalizes respondent.

- Right to contract. “That no man’s particular services shall be demanded, or property taken, or applied to public use, without the consent of his representatives, or without just compensation being made therefore.” Tenn. Const. art. 1 § 21. Respondent says petitioner cannot use his personal property and the public road unless he enters an insurance contract under duress. No authority exists for commissioner to make such demands or to criminalize use of the ordinary means of the day on the public right of way in exercise of individual rights of ingress and egress, and force the public into a contract with insurance companies or bonding agencies.

- Right to private property. This case is about privilege. The right to have and use private property in the constitution’s limited grant of taxing authority in Tenn. Const. Art 2 § 28, where ad valorem and privilege are the two types of tax. Privilege cases led by Phillips v. Lewis, 3 Shannon’s cases 230, 1877, explain privilege is upon commercial acts affecting the public interest. (TR p. 185, copy of case). The published case constitutes a jurisprudence that includes more than a dozen cases.

- Free use of public roads. “All roads, streets, alleys, and promenades where legally dedicated and thrown open for public travel or use free of charge shall be exempt from taxation.” T.C.A. §. 67-5-204. Respondent and deceived public servants in uniform deny petitioner’s “use free of charge” of the people’s roads (TR. p. 72, Tennessee transportation administrative notice; TR p. 254, Administrative notice; ingress-egress rights connecting movement rights to land.)

STATUTORY PARTICULARS

State law creates the privilege system upon commerce in Tenn. Const. Art. 2 § 28. The scope and reach of carrier regulation in title 65, chapter 15, carriers, and title 55, motor and other vehicles, exclude private use and do not make private use subject. No record exists of the Tennessee general assembly extending regulatory authority as upon private travel in the exercise of rights or personal necessities. That body is denied any such authority in the constitution, article 1, sects. 1 and 2, and Tenn. Const. art. 11 § 16. U.S. Const. Amend. IX protects unenumerated rights such as private travel, ingress-egress from one’s home or abode, and exercise of religion by using a car for religious purpose or fulfillment.

Tulis v. DOR – Motion to reconsider final order by agency

Enjoyment of petitioner’s common law and due process rights is not abrogated by the existence of state departments nor their rules for resolving conflicts.

a)(1) This chapter shall not be construed as in derogation of the common law, but as remedial legislation designed to clarify and bring uniformity to the procedure of state administrative agencies and judicial review of their determination and shall be applied accordingly.

(2) Administrative agencies shall have no inherent or common law powers, and shall only exercise the powers conferred on them by statute or by the federal or state constitutions.

T.C.A. § 4-5-103

Respondent revocation of commercial privilege creates a confrontation between LEOs and petitioner exercising non-abrogated and constitutionally protected travel, ingress-egress and communication rights. The officer will allege petitioner is criminally using the automobile under privilege, even though the citizen is not so using the conveyance under privilege.

Law requires traffic cases be acted upon pursuant to privilege law and the state’s obligation to exhaust its administrative remedies. Instead, law enforcement officers use criminal police power when law calls for economic police power exercise. Cops send allegations to Hamilton County general sessions court, criminal The city or county officer, claiming to represent the state as movant, refuses to fulfill the state’s exhaustion of administrative remedies requirement for alleged grievance against petitioner in the department of safety pursuant to UAPA. (TR p. 745, affidavit of criminal complaint against deputy for false arrest over damaged taillight)

Privilege concerns itself with transportation, a category of travel taxable and regulable as affecting the public interest. Private use, in contrast, apart from privilege is constitutionally protected. Whatever state lawyers and agency administrative judges may say, they are outside the scope of any department, whether safety or revenue, or any human authority, and stand as their own authority upon a hearing officer or proceeding, given that petitioner’s rights are recognized in the Tennessee bill of rights. All courts’ authority must conform to the edict “[t]hat all power is inherent in the people, and all free governments are founded on their authority, and instituted for their peace, safety, and happiness; for the advancement of those ends they have at all times, an unalienable and indefeasible right to alter, reform, or abolish the government in such manner as they may think proper” Tenn. Const. Art. 1 § 1.

Respondent denies that laws have scope and limit, and throws aside the possibility of private use of the people’s roads in the very statutes authorizing motor vehicle regulation. Enumeratio unius est exclusio alterius. — Specification of one thing is an exclusion of the rest. Peloubet’s Legal Maxims. A gun owner is free to carry, shoulder, load and to aim his weapon at a paper target and pull the trigger under Tenn. Const. art. 1 § 24, but when intending to shoot a deer for gain must have in possession a valid hunting license in that privilege. Respondent’s position about all use of an auto being in privilege would require it to assert that hunting licenses are to attach to every firearm in state of Tennessee and no one could bear arms without a hunting license in his possession at all times.

Cutting and gluing pipe under a sink is lawful and of right; only running a plumbing company in commerce requires the privilege. T.C.A. § 62-6-401. Cutting a son’s hair on the front porch doesn’t offend T.C.A. § 62-3-101 or the lawful privilege powers of the board of cosmetology.

Tennessee’s roadways are not state property for which respondent’s beggarly citizens are due to pay a rent. “The highways of the State belong to the people of the State” Dunlap v. Dixie Greyhound Lines, 178 Tenn. 532, 160 S.W.2d 413, 418 (1942).

Respondent refuses to consider the constitution as an authority, despite a statement of protest in one of its filings that the constitution is the first source of law in Tennessee (TR p. 913, response to petitioner MSJ). Respondent program violates petitioner’s constitutionally guaranteed rights apart from privilege. The program, and police power exercise based on its pretended claims widely disseminated among law enforcement agencies, constitutes a continuing harm apart from law deserving immediate relief.

ALL of government is a criminal enterprise…

If the public servants were actually properly educated on how it is supposed to work, instead on how they FEEL it should work, it wouldn’t be. Yet here we are!

Digging through congressional records has been beneficial in my journey – same fight as yours, only in northern California. What I found, is that ‘proof of financial responsibility’ is only required *after* an accident caused, and can *only be enforced for a 3 year period* if no more incidents arise during that 3 year period. Hope this helps!