A truck lies on its side after an accident, showing the danger shipping and transportation pose to the traveling public, thus giving reason why Tennessee and other states regulate driving and operating motor vehicles, which acts are commercial. Your license and tag give you access to for-profit use of the public right of way.

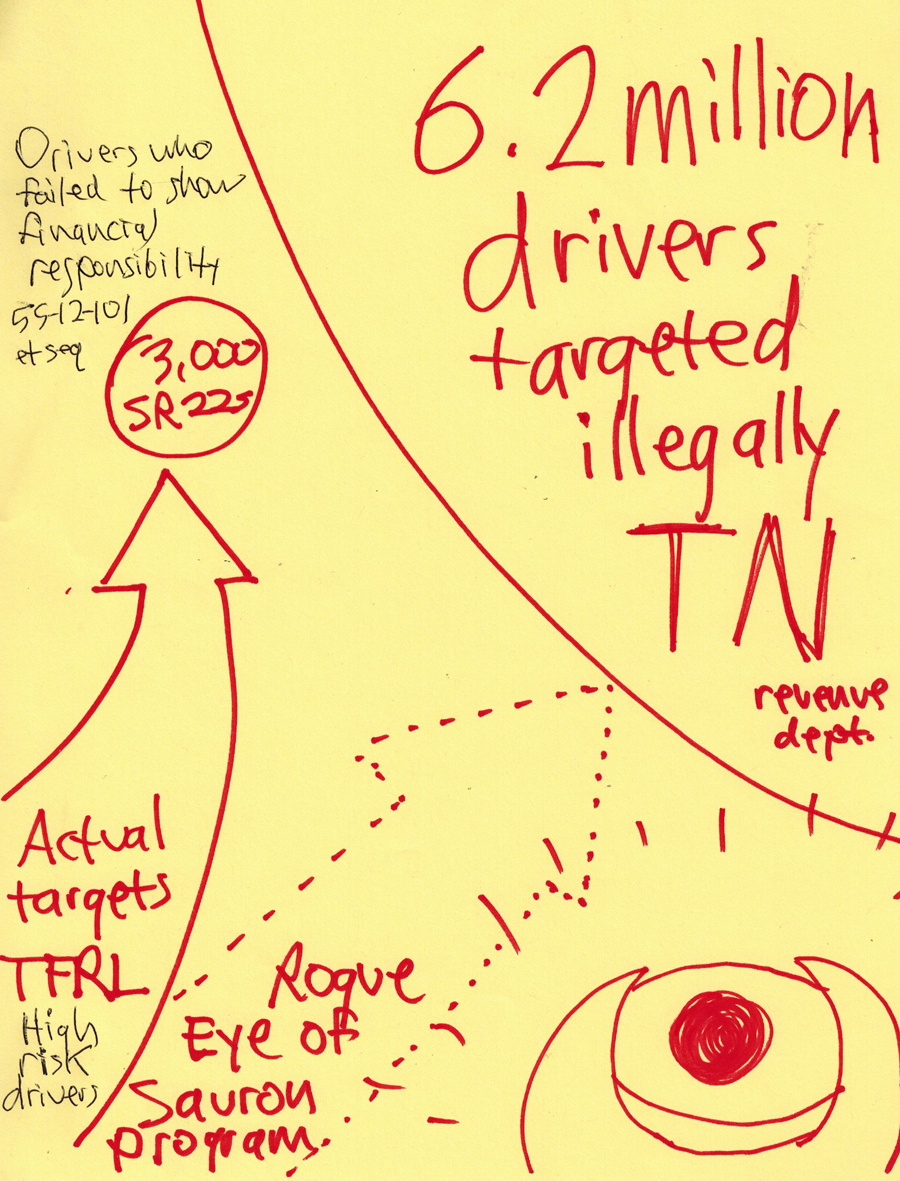

This sketch shows how department of revenue’s Eye of Sauron program operates not on 3,000 people subect to surveillance for insurance, but upon 6.34 million — illegally, criminally. I include this illustration in a 24pp. filing today in my fight against state fraud in Tulis v. DOR, docket no. 23-004CHATTANOOGA, Tenn., Tuesday, Oct.29, 2024 — The Tennessee commissioner of revenue is fogbombing me in my suit against him to overthrow his financial responsibility op against the public. He is saying there is no distinction between privileged and nonprivileged activity under Tennessee law..

That should be a shocker, when you think about. He’s saying there’s no difference between a taxability activity and a nontaxable activity. This guy sounds pretty much of a rogue, don’t you think, if he can’t see the line demarking the limit of his taxing authority. David Gerregano, in his filings against my honest reading of the Tennessee financial responsibility law of 1977, says there is no line between what’s taxable, and what’s not.

That means he’s a man who doesn’t know limits.

Tennessee revenue commissioner David Gerregano, center, meets with staffers. (Photo DOR)

Tennessee has two modes of taxation. One is ad valorem (the value added to a property because of commerce and business). The other is privilege. There is no other mode of taxation in Tennessee than these two. Few people understand privilege, meaning they have no way out of the fraud of what I call “commercial government.”

Just as podiatry, therapy, audiology, accounting, carpentering and plumbing are privileges, so is the occupation and calling — very honorably — of “driving and operating a motor vehicle.” This occupation gets an entire title in the Tennessee Code Annotated. That’s Title 55.

Cmsr. Gerregano says all use of the roads statewide is commercial. That’s because no one on the road travels on the road, or communicates on the road, or enjoys his rights on the roads, boulevards, lanes and freeways in state of Tennessee. All anyone can do is “drive a motor vehicle” on the road, meaning perform commercial activity behind the steering wheel.

I’ve filed a reply to his motion for summary judgment, part of which shows what a master fogbomber and liar he is to deny this vital distinction built into the law from Tenn. const. art. 2, sect. 28, on taxation. I explains all these useful facts to the commissioner of revenue, who wants to seem as ignorant as the rest of us about the real limits the law places on police power.

The distinction between privilege is not just in my imagination, as his stafff lawyer Camille Cline argues. The scenic highway act. The law regarding signs. The motor carrier law. The utilities law. The emergencies law. These sections make the distinction between the traveling and the shipping public. Without this distinction, we are in a police state. With the distinction we begin the long process of beating back the snarling hounds of commercial government with its roadside arrest and endless criminal prosecutions of the innocent.

What follows is from my amazing reply brief, with thanks to Ed Soloe, the gnome librarian, and Christopher Sapp, midstate bureau chief of Eagle Radio Network, for their contributions and time honing this filing.

‘Rights not implicated by regulation’

Petitioner has defended his right to communicate, travel, locomote, self propel using the public streets in exercise of ingress egress rights partly to show how careless and vicious respondent is in the matter over which the AHO ostensibly has authority — privilege under TFRL.

If the commissioner is willing to deny any constitutionally guaranteed right to travel not implicated by regulation, as divided out in State v. Booher, 978 S.W.2d 953, he is willing to deny rights under the privilege and dig up and relocate landmarks circumscribing financial responsibility laws.

Revocation of the Honda Odyssey minivan’s tag means the piece of personal chattel property is reduced to being merely an automobile. In the meantime, petitioner is suing to have the automobile reregistered for use as a motor vehicle. Petitioner’s sitting in the automobile and traveling down the road, apart from the privilege, respondent says, over these months of litigation, is a crime.

Right to freely use road arises from land right, land patents

Petitioner “alludes to purported ‘right[s] of ingress and egress’ with the implication that the Department’s suspension *** infringes upon such rights,” respondent says. He quotes the “sharp white line separating travel and transportation” paragraph from a relator filing and says it is “notable primarily for its lack of citation to any authority imparting the rights asserted therein.” He ignores a 5-page administrative notice citing 13 cases on soil rights protected by the enjoyment of ingress and egress rights.

The Ingress-egress right “appears to be *** somewhat antiquated.” He says Title 55 “does not address or recognize Petitioner’s asserted rights or otherwise indicate that such rights impact the registration of his motor vehicle in any way. *** [F]or the Petitioner to drive his vehicle on an office property and over the streets and highways of this state, he must comply with Tennessee’s laws addressing motor vehicle title and registration, including the Financial Responsibility Laws” (citation omitted) (pp. 14, 15). He cites Booher pointing out that “[t]he ability to drive a motor vehicle on a public highway is not a fundamental ‘right.’ Instead, it is a revocable ‘privilege that is granted upon compliance with statutory licensing procedures” Id. at 956 (internal citations omitted).

The law agrees with the Booher court’s distinction between driving and private travel. The acme of private travel, the case points out, is freedom to change domicile interstate. But many less dramatic types of travel in Booher are not implicated Or abrogated by Tennessee’s privilege rules.

The commissioner blunders by saying the law “imparts rights.” Law doesn’t impart rights. It recognizes them as pre-existing the codified law as inherent and in the nature of any man, woman, or person made in God’s image and free to live out God’s commandments and his or per private genius, duties or obligations. Properly read, the law should be seen as recognizing its own limits, beyond which there is freedom, liberty, the vast panoply of human life enjoyed by people who have a right to be left alone.

Respondent pretermits and denies nonprivileged use of auto-mobile personal property in the exercise of petitioner’s myriad God-given rights.

In this case he asserts all use of the road is by employers and employees, and by commercial users only in a corporate for-profit capacity (p. 13). The operation of motor vehicles is only activity he is willing to admit occurs on roads and boulevards. He is unwilling to admit that if one has ingress-egress rights, one has unfettered and free use of the public way. Petitioner establishes this legal precept in his administrative notice on ingress and egress rights, of record. Respondent quotes a court case cited by respondent in his administrative notice regarding soil rights – but fails to read it. “Her only private property in the street is her right of ingress and egress. She has no other right or interest in the street which is not to be enjoyed equally by each and every member of the community and the public generally.” Coyne v. City of Memphis, 118 Tenn. 651, 102 S.W. 355, 359 (1907) (emphasis in original from administrative notice, p. 2).

This quote supports petitioner’s right to direct his automobile freely as “enjoyed equally by each and every member of the community and the public generally.” Cops, deputies and troopers defraud and abuse the public by blocking their ingress-egress rights under the commissioner’s widely obeyed totalitarian theory.

‘Traveling & shipping public,’ a vital privilege distinction

State law, in fact, “does address or recognize” petitioner’s assertion about private rights in non-privileged self-propulation not affecting the public interest. “Public highways and streets are intended principally for public travel and transportation” Tenn. Code Ann. § 54-5-801 (emphasis added). Motor carriers (i.e., transportation) are regulated in chapter 15 of T.C.A. § Title 65 to “(1) Regulate, foster, promote and preserve proper and economically sound transportation and authorize and permit proper coordination of all transportation facilities; (2) Relieve existing and future undue burdens upon the highways arising by reason of their use by motor vehicles; (3) Protect the welfare and safety of the traveling and shipping public in their use of the highways, and in their contact with the agencies of motor transportation and allied occupations; and (4) Protect the property of the state and its highways from unreasonable, improper or excessive use” T.C.A. § 65-15-101 (emphasis added).

To “provide information in the specific interest of the traveling public, the commissioner [of transportation] is authorized to maintain maps and to permit informational directories” at “safety rest areas” § 54-21-110. Information for traveling public. The Scenic Highway System Act of 1971 serves pleasure users of roads. The act limits commercial messaging “for the recovery and conservation of natural scenic beauty along designated scenic highways” T.C.A. § 54-17-104.

Scenic routes are “designated to offer alternative travel routes to the high-speed, heavily traveled highways in the state” used by heavy commerce. Scenic highways “shall provide the motorist with safe and relaxing routes of travel” for pleasure. Scenic highways are off the track beaten down by trucks. The plan shall include “[t]he major routes of travel of tourists through the state so as to maximize the use of scenic highways by visitors in the state” T.C.A. § 54-17-105 (emphasis added).

“In the event of a transportation system failure, an imminent threat of a failure, or other emergency that the commissioner reasonably believes would present a hazard to the traveling public or a significant delay in transportation, then the commissioner shall have the authority to enter into contracts narrowly tailored to remedy the actual or imminent failure or other emergency” § 54-1-135 (emphasis added). Transportation system failures and emergencies; authority of commissioner; contracts.

“The monthly county court is vested with the power *** to establish road improvement districts for the purpose of building and maintaining public roads in the road improvement districts, and building bridges, culverts, and levees on the roads and to locate and establish the roads, or provide for these things being done whenever they are of public utility or conducive to the public welfare” T.C.A. § 54-12-101 (emphasis added). “All roads, streets, alleys, and promenades where legally dedicated and thrown open for public travel or use free of charge shall be exempt from taxation” T.C.A. § 67-5-204 (emphasis added).

Private blockages of the road are prohibited. “(a)(1)(A) The department is authorized to remove, store, sell and dispose of personal property encroachments on the rights-of-way of highways under its jurisdiction at the expense of the owner. (B) If the encroachment presents an immediate danger to the traveling public, the department may remove the encroachment without prior notice to the owner. *** (C) If the encroachment does not present an immediate danger to the traveling public and the owner’s name and address can be ascertained by reasonable inquiry” T.C.A. § 54-5-136 (emphasis added). Under color of law, blockages of the public right of way by respondent and law enforcement agencies are an oppression likewise prohibited.

Rights of way = ‘transmission of public intelligence’

Roads serve as means of transmission of public intelligence and communication.

“Utilities are an integral part of the full use of the public rights-of-way, all serving the public interest. *** Since 1905 under the holding in Frazier v. East Tennessee Tel. Co., 115 Tenn. 416, 90 S.W. 620, 3 L.R.A.,N.S., 323, Tennessee has been committed to the view that the use of public rights-of-way by utilities for locating their facilities is a proper highway use subject to their principal purpose as travel and transportation of persons and property. ‘Clearly since the Cater decision in 1895, Minnesota has been definitely committed to the view that the use of rights-of-way by utilities for locating their facilities is one of the proper and primary purposes for which highways are designed even though their principal use is for travel and the transportation of persons and property. Furthermore, the import of that decision is a clear recognition that the use of highway rights-of-way for the transmission of public intelligence and public utility services confers important and direct benefits upon the public and that such use is not solely for the benefit and convenience of the utilities’”

Pack v. S. Bell Tel. & Tel. Co., 215 Tenn. 503, 511, 387 S.W.2d 789, 792–93 (1965) (emphasis added).

Respondent says only “driving *** his vehicle” is allowed petitioner as permissible travel. “However, in order for the petitioner to drive his vehicle on and off his property and over the streets and highways of this state, he must comply with Tennessee laws addressing motor vehicle title and registration,” he says, citing State v. Booher, 978 S.W.2d 953.

Streets and roads are not owned and controlled by respondent or the state. They are owned by the people, in whom “all power is inherent” and upon which authority “all free governments are founded *** and instituted for their peace, safety, and happiness” Tenn. const. art. 1, sect. 1. Respondent regulates roadways’ commercial use by drivers and operators. The state is guardian. It is trustee.

The constitution and a right reading of law admit no obstruction of free movement that respondent’s motion threatens. The right of free communication by using ingressing and egressing automobiles is “enjoyed equally by each and every member of the community and the public generally,” apart from the state, apart from the commercial privilege system with its truck drivers, haulers and rigs. Respondent and policy-following police officers and deputies constitute an “encroachment [that] presents an immediate danger to the traveling public.”

Since revocation, petitioner uses his minivan as an automobile, apart from privilege. Respondent describes this criminal activity as “driving an unregistered vehicle.” It’s not a vehicle, registration revoked. Petitioner is not driving it, not engaged in the acts requisite for privilege, per Phillips v. Lewis, 3 Shannon’s cases 230, forbidden under Tenn. Code Ann. § 55-50-504. He’s merely enjoying his rights in its movement down the roadway.

With no warrant, Brandon Bennett, a Hamilton County, Tenn., sheriff’s deputy, gets set to arrest me Nov. 22, 2023, exercising my right of ingress and egress from my house, obstructing the public road as if he were a bandit. (Photo David Tulis)

If the commissioner is hostile to fundamental ingress-egress rights — implying as they do the absolute liberty of movement upon the roads without abrogation, interruption or seizure — he is disposed to be careless about controlling statute dealing with the exercise of the driving privilege under TFRL and Atwood.

Conclusion

Relator emphasizes the constitutional issues to show bad faith by respondent, a willingness to violate the public trust against members of the public outside Atwood’s authority. The hearing officer may opt to punt this case by finding he has no subject matter jurisdiction, since hearings in TFRL are heard in department of safety and proceedings are void if not authorized by law.

(a) Except as otherwise specifically provided, the commissioner shall administer and enforce this chapter, may make rules and regulations necessary for its administration, and shall provide for hearings upon request of persons aggrieved by orders or acts of the commissioner [safety] under this chapter; provided, that the requests are made within twenty (20) days following the order or act and that failure to make the request within the time specified shall without exception constitute a waiver of the right.

(b) Any person aggrieved by an order or act of the commissioner under this chapter may seek judicial review of the order or act as provided by § 4-5-322.

55-12-103. Administration; hearings; appeal and review (emphasis added)

No provision in Atwood allows for hearings in revenue. UAPA specifically declaims it applies to revenue rulings. Yet the proceedings have been under color of UAPA. On this point alone of subject matter jurisdiction, the hearing officer can smash the illegal and unconstitutional Sauron program. Petitioner’s citations of nearly 30 other violations add to the debris and dust of the tower’s crashing down.

David’s reply in financial responsibility lawsuit

This case is a grotesque scandal he has denied the past 461 days since petitioner filed notice. The program is an aberration, a picture of in-grown corporate capture of a government agency in departure from law. Respondent views the T.C.A. § 55-12-214 ban on new requirements as inconsequential as a piece of lint or a bottlecap.

Brad Buchanan, chief hearing officer Tennessee department of revenue, oversees Tulis v. department of revenue.

Respondent’s cases cited describe summary judgment (p. 4), rules for statutory construction (p. 10), ingress-egress and travel rights (pp. 14, 15). All the court cases dealing with financial responsibility are in support of petitioner, and he ignores them.

Petitioner challenges the hearing officer to be true to his word about the case. Petitioner demanded his recusal in this unprecedented first-impression suit on grounds of interest, prejudice, amity, familiarity and institutional bias. The AHO refused, saying he will rule on the law and facts truly, without flinching, wherever they take him. This case demands that he lay all hope, comfort and affinity aside on realizing petitioner is right about grievance personal and representing those of Tennesseans as a whole. This petition against Eye of Sauron empowers him to favor the rules of statutory construction that forbid party spirit when justice and jurisprudence itself are at stake.

In light of the forgoing, petitioner demands the hearing officer reject the commissioner’s motion for summary judgment, and give recognition and favor to petitioner’s.

The People beat themselves by assuming that they have a state assembly that they have authorized to over-rule and/or dictate to them as if they are chattel property of a mere corporation. AKA, the public.