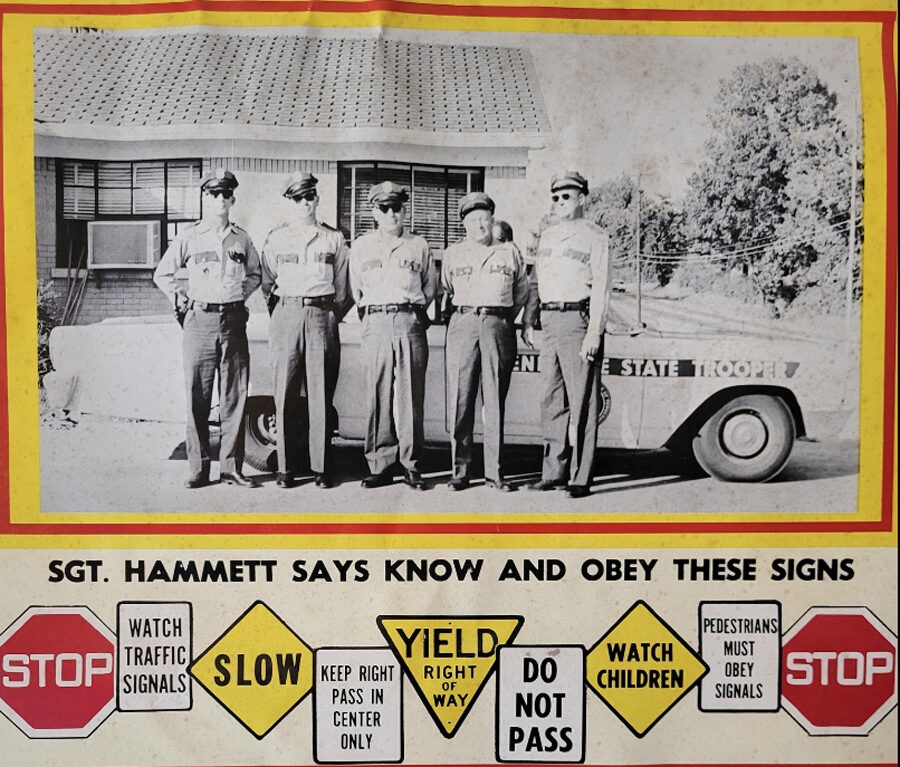

Tennessee state troopers operate outside the law, like a gang. These troopers appear in a 1966 calendar. I am asking the federal court of appeals to force Hamilton County, Tenn., to respect the due process rights all licensees have, that is, to have accusations about their use of a driver license be heard administratively under UAPA, the uniform administrative procedures act, and not criminally. Troopers, cops and deputies prosecute private travelers under the trucking statutes criminally, and until now no one has made proper objection to this longstanding use of violence, harm and prosecution. (Photo DOSHS)

CHATTANOOGA, Tenn., Thursday, Aug. 14, 2025 — Right now I am waiting for a reply from the Hamilton County attorney’s office regarding my brief on appeal in the 6th circuit of the federal appellate courts. I am suing the county, plus the sheriff and a deputy for false imprisonment and false arrest, attacking the foundation of criminal traffic stops across the land.

They are all under criminal authority that is, as they say, ultra vires. That means outside the scope of law. Traffic stops under Tennessee’s legal infrastructure supposed to be administrative proceedings in the department of safety, as all matters pertaining to a license — from issuance, suspension or revocation — are purely administrative, the courts have ruled. That means it’s improper to criminal charge, arrest, jail and prosecute someone for a damaged taillight, as I was in a Nov. 22, 2023, encounter with a Hamilton County sherif’s deputy.

The case Tulis v. Bennett is without precedent, meaning it obtains no media coverage except for the press coverage I have given on my platforms. It proposes a total shakeup of the system of criminalized commercial government. It would take the violence and injury out of the long custom and usage of “traffic arrests” and will take a great deal of ingenuity and connivance for the court to throw out. The issues I raise are foundational as to privilege, driving being one of them no different than the privilege of plumbing, hairdressing, embalming or accounting.

Brandon Bennett launches a criminal case that the law in Tennessee is really an administrative matter under the doctrine of exhaustion of administrative remedies. My petition is without precedent, and is being heard in the 6th circuit court of appeals. (Photo David Tulis)

***

Argument

SUMMARY The use of criminal police power — including seizure of the person and initiation of criminal proceedings — is suitable only where the alleged conduct constitutes a crime under statutory or common law. A broken taillight, while a regulatory defect in a licensed occupation, constitutes at most a civil infraction or administrative breach. It does not create a public offense and thus does not justify invocation of criminal police power limited under T.C.A. § 40-7-103 or under the Fourth Amendment.

The complaint is premised on the truism that “driving or operating a motor vehicle is a privilege,” or an agreement in equity between the state and a citizen, with due process afforded the citizen under the rules governing each state-owned occupation. That is, under UAPA and the obligation of the movant to exhaust administrative remedies if aggrieved.

Appellant accepts defendants’ own premise: that operating a motor vehicle is a regulated privilege. Accordingly, enforcement must comply with administrative process, including notice and opportunity for hearing under the UAPA. Defendants instead invoked criminal power without exhaustion of administrative remedies, converting a regulatory infraction into an unlawful seizure.

Complaint establishes it is improper to use criminal, peacekeeping, conservator of the peace authority to arrest appellant under authority of the sheriff law. “The sheriff and the sheriff’s deputies are conservators of the peace, and it is the sheriff’s duty to suppress all affrays, riots, routs, unlawful assemblies, insurrections, or other breaches of the peace, detect and prevent crime, arrest any person lawfully, execute process of law, and patrol the roads of the county” T.C.A. § 8-8-213 Powers as conservator of the peace

- THE NATURE OF TITLE 55: ADMINISTRATIVE, NOT CRIMINAL

Controversies over activities under license are administrative in nature. “[T]he grant or refusal of a license to use public highways in commerce is purely an administrative question” McMinnville Freight Line, Inc. v. Atkins, 514 S.W.2d 725, 726–27 (Tenn. 1974). “[T]he Utilities Commission has never been held by this Court to be restricted by the technical common law rules of evidence in determining purely administrative questions, and we have held that the grant or refusal of a license to use public highways in commerce is purely an administrative question.” Hoover Motor Exp. Co. v. R.R. & Pub. Utilities Comm’n, 195 Tenn. 593, 616, 261 S.W.2d 233, 243 (1953) (emphasis added). The commissioner of safety is charged with overseeing grant, suspension or revocation of driver licenses. T.C.A. §§ 55-50-202 and -502

Hamilton County sheriff’s office records show no evidence of authority to administer titles 55 or 65, chapter 15, by way of agreement, delegation, covenant, contract or order (Doc. 1 PageID 26 ¶ 96). It prosecutes appellant in the name of the state.

- THE EXHAUSTION DOCTRINE IN TENNESSEE AND FEDERAL LAW

Enforcement of motor vehicle regulation — by defendants’ own theory a matter of privilege — is administrative, and must originate DOSHS, not roadside with cuffs and criminal process.

Both Tennessee and federal courts have long held that judicial relief is premature where the state or a party has not first pursued its administrative remedy. McKart v. United States, 395 U.S. 185 (1969) (“that no one is entitled to judicial relief for a supposed or threatened injury until the prescribed administrative remedy has been exhausted”) and Mathews v. Eldridge, 424 U.S. 319 (1976) (evidentiary hearing prior to final order in terminating benefits “would entail fiscal and administrative burdens out of proportion to any countervailing benefits”). The doctrine of exhaustion on discretion prevents a party from “leaping prematurely to a judicial venue” Portela-Gonzalez v. Sec’y of the Navy, 109 F.3d 74, 80 (1st Cir. 1997) (“Insisting on exhaustion forces parties to take administrative proceedings seriously, allows administrative agencies an opportunity to correct their own errors, and potentially avoids the need for judicial involvement altogether. Furthermore, disregarding available administrative processes thrusts parties prematurely into overcrowded courts and weakens an agency’s effectiveness by encouraging end-runs around it” Id. at 79.

This rickety truck from California is put out of service by a Tennessee trooper in that officer’s proper use of safety and revenue collection authority. (Photo DOSHS)

“Both courts and legislatures have recognized that the exhaustion doctrine promotes judicial efficiency and protects administrative authority[.]” Colonial Pipeline Co. v. Morgan, 263 S.W.3d 827, 838 (Tenn. 2008). “When a statute provides for an administrative remedy, an aggrieved party must ordinarily exhaust the remedy before seeking to utilize the judicial process. Thomas v. State Bd. of Equalization, 940 S.W.2d 563, 566 (Tenn. 1997); Bracey v. Woods, 571 S.W.2d 828, 829 (Tenn. 1978).” Ready Mix, USA, LLC v. Jefferson County, Tennessee 380 S.W.3d 52, 63, 64.

Speaking from criminal jurisdiction, the court says the deputy justly arrests appellant; Mr. Bennett has probable cause, seeing appellant moving down the road behind the steering wheel of an automobile with a functioning but damaged taillight. But appellant acts to preserve his rights and rebuts the prima facie evidence of commerce (department of revenue registration tag on auto rear bumper). It is significant that the Hamilton County district attorney refuses to ratify Mr. Bennett’s actions done against appellant (Doc. 1 PageID # 21ff).

A damaged taillight is a misdemeanor, the court says, ignoring privilege infrastructure and its powerful federal context, and Mr. Bennett’s actions are no offense to U.S. Const. Amend. IV.

- UAPA DUTY PRECEDES 4TH AMENDMENT

However, complaint claims defenses that precede U.S. Const. Amend. IV jurisprudence cited by the court. Defendants inject themselves into a DOSHS controversy. That dispute is not criminal. It is civil by privilege law’s design, affording appellant due process protections in protocols laid out for a contested case in agency. T.C.A. § 4-5-301 et seq. His taillight dispute with state of Tennessee’s department of safety is not ripe for criminal prosecution by defendants. Until movant state exhausts its administrative remedies under title 55 for wrongdoing under rules for privilege taxable activity, defendants’ policy and use of wristcuffs, jail and filing criminal charges with district attorney are a compensable tort.

- CASES OFF POINT

The exhaustion doctrine and the role of UAPA is waived by cases used to dismiss the complaint. The court’s authorities are about enforcement of criminal authority in “a civil traffic violation” (Whren v. United States, 517 U.S. 806, 808 (1996)).

These cases are Atwater v. City of Lago Vista, 532 U.S. 318(2001), Virginia v. Moore, 553 U.S. 164 (2008), State v. Lozano, No. M201701250CCAR3CD, 2018 WL 4275919 (Tenn. Crim. App. Sept. 7, 2018), Crouch v. Elliott, No. 4:04-CV-96, 2005 WL 2122057 (E.D. Tenn. Sept. 1, 2005), State v. Williams, No. M2012-00242-CCA-R3CD, 2012 WL 4841547 (Tenn. Crim. App. Oct. 3, 2012), Barnhart v. Dilinger, No. 3:16-CV-2597, 2020 WL 7024670, at *1 (N.D. Ohio Nov. 30, 2020), State v. Williams, No. M2012-00242-CCA-R3CD, 2012 WL 4841547 (Tenn. Crim. App. Oct. 3, 2012) and Id. Booher. Parties in these cases waive the exhaustion of administrative remedies issue.

This case has other elements tending toward removal of tyranny and oppression. Its demands are supported by administrative notice informing defendants years ahead of time of this lawsuit and its twin demands for relief —from general warrants and criminal traffic cases, each pretermitted by the court despite the public interest

Two unrebutted administrative notices served prior to the arrest put defendants on awares about Tennessee transportation law at titles 55 and 65, chapt. 15, and their federal law integration shown above (also Doc. 1, pageID # 9, FN2). Had Mr. Bennett obeyed the law he swore to uphold, cited in EXHIBIT No. 2, administrative notice on arrest powers, he would have acted in a way to have avoided putting his personal estate in jeopardy by making an arrest for a non-public offense on his own authority. Mr. Bennet would’ve gone to a Hamilton County magistrate, drafted and sworn an arrest complaint for a crime committed by David Jonathan Tulis (or the unnamed white male driving a Toyota RAV4 with a given VIN and plate). The magistrate most certainly would have denied him an arrest warrant, would have clued him in that a damaged taillight is not a crime for which an arrest warrant shall issue despite sworn complaint. T.C.A. § 40-6-203. Examination of affiant.

Defendants traffic stop program short-circuits well-known protections for members of the public, and county employees in public service who face the onus of making false arrests in hopes no one will sue.

- WELL KNOWN LAW — BUT NOT BY BENNETT ET AL

The court ignores the totality of factual circumstances that defendants knew driving a motor vehicle is a privilege. It ignores they knew by well-known and public law and by notice that titles 65, chapt. 15, and 55 regulate privilege taxable activity, knew by law and notice a damaged taillight is not a crime, and acted against him criminally in bad faith.

The court dismisses the complaint by rejecting privilege law, UAPA and federal hegemony over vehicle regulation cases that “foreclosed” appellant’s case. “Plaintiff based his theory off how a federal statute defines ‘motor vehicle’ *** (See Doc 1, at 13 n. 3 (citing 18 U.S.C. § 31)). Plaintiff argues that his car is not a ‘motor vehicle’ unless he is using it for commercial purposes under this federal definition. In addition to not making logical sense, Plaintiff’s theory is foreclosed by case law.”

Despite what Plaintiff may believe, his theory that he does not need a driver’s license when traveling for personal reasons is not new or persuasive. It is frequently raised and just as frequently rejected. Tennessee courts have addressed this argument and found it “utterly without merit.” *** Federal courts also frequently and summarily reject Plaintiff’s theory.

Doc. 37 PageID ## 337, 338

Respectfully, defendants and the court aren’t “making logical sense” to insist on title 55 as ground for criminal prosecution of appellant, then prejudicially ignore the entirety of a licensee’s due process protections under that title in department of safety. Citing state and federal cases wherein the issues of this case are waived suggests the court is more keen on upholding judicial policy, even judicial fictions, than making Tennessee federally integrated transportation law work. Its statements smack of judicial impressionism, broad strokes without detail. In this policy, all automobile use is regulable, under title 55, but don’t bring up title 55 commerce and or insist that noncommerce must exist; no one is free (any more) to use the public road apart from general warrants and commercial regulation by presumption.

DOSHS has authority over motor vehicle privilege. Department of revenue regulates registration of motor vehicle. T.C.A. § 55-4-101. FN 15 Defendants’ arrest authority for alleged misdemeanor crimes is limited under U.S. Const. Amend. IV, Tenn. Const. Art 1 § 7 and under T.C.A. § 40-7-103, warrantless arrest by officer.

15 (1) As a condition precedent to the operation of any motor vehicle upon the streets or highways of this state, the motor vehicle shall be registered as provided in this chapter. (2) The registration and the fees provided for registration shall constitute a privilege tax upon the operation of motor vehicles.

T.C.A. § 55-4-101 (emphasis added)

- IF EXHAUSTION, UAPA WAIVED, NO CONFLICT WITH CASES

This case challenges the presumption not challenged in other actions, that criminal enforcement authority is premature when clear, well-known law on privilege taxable activity requires movant state to exhaust its administrative remedies before petitioning for adjudication from a court in the state’s judicial department. Appellant’s arrest was without warrant and was unreasonable statutory construction of privilege law in title 55 cited by the deputy and procedures for handling controversy thereunder.

The court refuses to consider appellant’s extensive references to federal law (see Doc. 1, PageID # 9). U.S.C. 49, transportation, is echoed by federal criminal law, which appellant also cites (18 U.S.C. § 31 definitions, “(6) Motor vehicle.–The term “motor vehicle” means every description of carriage or other contrivance propelled or drawn by mechanical power and used for commercial purposes on the highways in the transportation of passengers, passengers and property, or property or cargo.”)

When read in pari materia, Atwater and Moore and state privilege law regulation are not necessarily in conflict. Appellant’s claims about due process precede questions of legality of criminal prosecution. Other appellants waived the issues that make this case an apparent first.

- BOOHER CASE

In a footnote, the court says that Tennessee courts declare that automobile = motor vehicle, citing Id. Booher at 956 (Tenn. Crim. App. 1997), a prevailing authority. “Plaintiff was arrested for a violation of Tennessee law. Tennessee law defines the term ‘motor vehicle’ broadly and without any reference to commerce. See Tenn. Code Ann. § 55‐1‐103(c). Tennessee courts have been clear that automobiles are motor vehicles as defined by this statute. See State v. Booher, 978 S.W.2d 953, 956 (Tenn. Crim. App. 1997) (rejecting argument that an automobile is not a ‘motor vehicle’ and concluding that ‘appellant’s 1985 Dodge Daytona is a motor vehicle).” (Doc. 37, PageID # 337)

Tennessee courts have read Booher to mean that all automobiles are motor vehicles under T.C.A. § 55‐1‐103(c), regardless of commercial use. But Booher does not address whether enforcement of title 55 against a licensee requires administrative process before resort to criminal arrest — the core issue here.

The claim that an automobile is always a motor vehicle is belied by the history of motor vehicle regulation since 1905, as noted above and in appendices. Neither GA nor the U.S. congress has voted to “regulate” private activity on the public road — ever. The record of laws in this petition show regulation is on business use, not on constitutionally protected or free use, as that on Nov. 22, 2023, by a press member. Such judicial canoodling in disallows the law to operate and protect constitutionally guaranteed, God-given liberties.

The pretense of universal obligation upon motorists — in Tennessee forbidden by Tenn. Const. Art. 11 § 16 — is belied by the nature of state privilege or excise. FN 16 Saying all use necessarily is under license is like saying all speech necessarily is under license, or that all children conceived necessarily are under license, all apart from any law. An automobile becomes a motor vehicle when the owner applies and pays to register it with the department of revenue for the purpose of privilege taxable activity. The owner registers the private conveyance to make it an “instrumentality of interstate commerce or a thing in interstate commerce” United States v. Lopez, 514 U.S. 549, 559 (1995).

16 Tenn. Const. Art. 11 § 16: The declaration of rights hereto prefixed is declared to be a part of the Constitution of this State, and shall never be violated on any pretense whatever. And to guard against transgression of the high powers we have delegated, we declare that every thing in the bill of rights contained, is excepted out of the General powers of government, and shall forever remain inviolate.

If appellant has done that, he has rights under exhaustion. If he hasn’t done that and is not licensed or registered, he has rights to be approached by the officer for crimes or public harm threats only. The court’s statements about motor vehicle being “[defined] broadly” and “without any reference to commerce” in T.C.A. § 55-1-103(c) are misleading, as if the court were trying to get away with defining dog as “an animal with four legs.” FN 17

17 “[Transported]” appears in the definition of vehicle, making vehicle commercial.

(9) “Commerce” means:

-

(A) Trade, traffic, and transportation within the jurisdiction of the United States; between a place in a state and a place outside of the state, including a place outside the United States; and

-

(B) Trade, traffic, and transportation in the United States that affects any trade, traffic, and transportation in subdivision (9)(A)

T.C.A. § 55-50-102 (emphasis added)

A motor vehicle is a vehicle which is a freight motor vehicle. These three terms are synonyms, and describe instrumentalities in commerce as defined by T.C.A. § 55-50-102(9)(A) and (B).

(c) “Motor vehicle” means every vehicle that is self-propelled, excluding electric scooters, motorized bicycles, personal delivery devices, and every vehicle that is propelled by electric power obtained from overhead trolley wires. “Motor vehicle” means any low speed vehicle or medium speed vehicle as defined in this chapter. “Motor vehicle” means any mobile home or house trailer as defined in § 55-1-105.

-

(e) “Vehicle” and “freight motor vehicle” means every device in, upon, or by which any person or property is or may be transported or drawn upon a highway, excepting devices moved by human power or used exclusively upon stationary rails or tracks.

T.C.A. § 55-1-103 (emphasis added)

Booher says that driving and operating a motor vehicle are a privilege, and that privilege regulation doesn’t implicate the right to travel, meaning doesn’t offend the right to private travel. Travel means self-propulsion, movement, ingress-egress – and more, Booher says. “Travel, in the constitutional sense, however, means more than locomotion; it means migration with the intent to settle and abide” Id. Booher at 955. This sentence has been relied on for 38 years for the prosecutorial and judicial doctrine bringing disorder to the law. It’s craftily written to be read as saying “ONLY migration is recognized under the constitution as travel” and not locomotion. It doesn’t actually say that. It says locomotion is travel, and migration is travel. The latter does not under the rules of construction and our constitutional protections delete the former. If it’s true that, as the court indicates, automobile = motor vehicle, it follows in Booher’s judicial casuistry that privilege = nonprivilege, that taxable = nontaxable, untenable propositions for an honest court.

Appellant sues for recognition that driving a motor vehicle is a privilege, with which statement defendants agree.

Mr. Bennett cites title 55. Its entire corpus is privilege law. It is commercial under Tenn. Const. Art. II § 28 and 49 U.S.C. transportation. Titles 55 and 65, chapt. 15, are federal because Tennessee government is member of the unified carrier registration system set up by the U.S. department of transportation, in accordance with 49 U.S.C. § 13908. “The commissioner of revenue is authorized to participate in the unified carrier registration plan and agreement established in accordance with 49 U.S.C. § 14504a, and to file on behalf of this state the plan required by 49 U.S.C. § 14504a(e)” T.C.A. § 65-15-101.

Notices are EXHIBIT No. 1 (Doc. 1 PageID # 43) showing the “public offense” standard of warrantless misdemeanor arrest. EXHIBIT No. 2 showing privilege operations in titles 65 and 55 in the occupation of transportation (Doc. 1 PageID # 59).

Defendants waived any right to dispute their myriad citations to law and court rulings.

- COURT’S ERRONEOUS CRIMINAL AUTHORITY PREMISE

The trial court views the case solely through Tennessee’s and sheriff’s criminal authority. The premise of the complaint is that if appellant has done wrong in a relationship with the state, the state’s remedy must first be under administrative law. “Traffic stops” are regulatory and administrative license agreement enforcement. Mr. Bennett crossed the line from administrative enforcement to criminal enforcement without a legal ground on which that criminal authority might land.

A damaged taillight is not in title 39, the criminal code. He violated the UAPA by denying his accused access to that remedy first (Doc. 1, PageID #3, ¶7). He followed county and Garrett departmental policy premise of criminal authority applied upon an alleged administrative equipment defect. Defendants do not possess trooper authority under T.C.A. § 40-7-103(c) to pull over a motor vehicle without probable cause to ask showing of a driver license.

- APPELLANT RELIED ON DEFENDANTS’ ACCEPTANCE

Appellant’s allegedly criminal acts are without mens rea. He uses the roads with a clear conscience, and he relied on defendants’ acquiescence to properly served and notoriously published legal notice as to relevant law on privilege taxable activity and on arrest. They are on record as understanding, agreeing and acquiescing to the laws.

The complaint alleges the arrest had no probable cause, given the law, and given defendants’ knowing the law and knowing at least putatively their defendant’s state of scienter regarding alleged infractions of the title 55 light law. The court unjustly allows defendants to escape after appellant had relied on their acquiescence to his two notices, establishing his state of mind and the laws cited regulating their actions. Under notice, they would appear barred by estoppel by entrapment from imprisoning and arresting him for alleged privilege wrongdoing where mens rea doesn’t apply. FN 18

18 If an act is a crime, the accuser is required to allege knowingness or intentionality.

(a)

(1) A person commits an offense who acts intentionally, knowingly, recklessly or with criminal negligence, as the definition of the offense requires, with respect to each element of the offense. ***

(b) A culpable mental state is required within this title unless the definition of an offense plainly dispenses with a mental element.

(c) If the definition of an offense within this title does not plainly dispense with a mental element, intent, knowledge or recklessness suffices to establish the culpable mental state.

T.C.A. § 39-11-301. Mental state (emphasis added)

- CRIMINAL AUTHORITY MISDIRECTED

Mens rea or guilty mind is requisite in all allegations of crime in title 39, the state criminal title. Titles 55 and 62 are not in the criminal code. The criminal code where all criminal charges must allege and prove intent excludes damaged taillights and such defects or conditions that are addressed by privilege regulation outside the criminal code. Bennett wants to attack a member of the public his way, for his own convenience — using regulatory law to allege a crime AS IF it were in title 39, but making no allegation of mens rea, which is an essential element of a criminal charge. Dismissal lets defendants go, free to abuse the public with a mix of criminal and administrative law, provisions selected prejudicially against appellant to deny him due process.

Appellant is not proposing the state be denied its police power to regulate or to settle its grievances against citizens. It enforces license and privilege agreements people make with its agents via UAPA, civil administrative enforcement in contested cases in agency. “Soft” authority is backed ultimately by the “hard” misdemeanor penalty that it can exercise in circuit or chancery court or by petition to the district attorney for criminal prosecution. That sanction exists in virtually every privilege extended to a member of the public. Criminal sanction is at the end of any dispute process with a licensee in the state’s ultimate interest to protect the collect, uphold the health, safety and welfare of the public. FN 19

19 Violation of the tattoo privilege law is a misdemeanor. The envisions no enforcement by deputies or city police officers under criminal authority, but a UAPA hearing under the tattoo board:

(a) Any person who does not obtain a permit as required in § 62-38-202 or whose permit has been revoked or suspended and who continues to tattoo or operate a tattoo establishment commits a Class B misdemeanor *** .

(b) Any suspension or revocation may be appealed to the local health officer who shall then conduct a hearing of the appeal in accordance with the Uniform Administrative Procedures Act ***.

(c) The department is encouraged to utilize its existing resources to collaborate with local law enforcement to identify and assess administrative penalties against persons who violate this part.

T.C.A. § 62-38-208

A damaged taillight is not a crime, according to the history of motor vehicle regulation, and the sufficient complaint (Doc. 1). Mr. Bennett unreasonable arrests, imprisons, handcuffs, jails and criminal prosecutes appellant when his principal, state of Tennessee, has law letting its agents to enforce the statewide privilege in department of safety. A civil summary violation, infraction or offense, under title 55, under title 65, is not a crime, as defendants know.

Mr. Bennett declaimed his authority under title 55 by saying appellant is not involved in commerce. If not, what then? He makes an arrest absent a crime, with the court’s approval. The court should see he denies his own probable cause in that statement. He lacks criminal authority as he had not seen appellant commit a felony or misdemeanor. He lacks authority under T.C.A. § 40-7-103 to make a judicial determination a crime has taken place, and that appellant did it. He theoretically might have had authority under title 55, but defendants waive that issue.

As a private citizen under T.C.A. § 40-7-109, arrest by private person – grounds, Bennett “may arrest another (1) for a public offense committed in the arresting person’s presence” or (2) a felony. A damaged taillight is not a “public offense” under T.C.A. § 40-7-103 or -109, actionable by Mr. Bennett either in officer or in his private capacity as a man or citizen under sect. 109. The court says Atwater destroys the requirement Mr. Bennett make the “public offense” test as an officer making a warrantless misdemeanor arrest.

It says nothing about T.C.A. § 40-7-109, the private citizen authority for a warrantless arrest. Mr. Bennett is sued in his person because that’s the capacity in which he acted, seizing a citizen without a public offense to justify the seizure.

Appellant doesn’t waive issues waived by parties in cases cited by the court in dismissal. The laws defendants invoke to criminally jail and prosecute him are not within their purview or grant, except by long custom of which the people in Hamilton County have grown weary and angry.

The motor vehicle law is federal privilege management of motor carriers and motor vehicles (Doc. 1 PageID # 9). County deputies and city cops have no authority to administer — with criminal “conservator of the peace” police power, no less — the tax authority given state troopers in § 4-7-101 et seq and title 65, chapter 15. Criminal enforcement by defendants denies appellant his due process rights to be protected under UAPA by channeling state enforcement through structured administration rather than streetside imprisonment and arrest, properly described as “poaching” (Doc. 1, PageID # 12 ¶37).

In sum: Appellant’s theory is not novel, but simply unwaived. Courts routinely presume criminal authority in traffic enforcement by stipulation or inattention. Here, appellant preserves the issue, pled it with clarity in sessions court after his arrest (APPENDIX EX. No.1), and provided unrebutted documentation. That is enough to warrant reversal and remand.