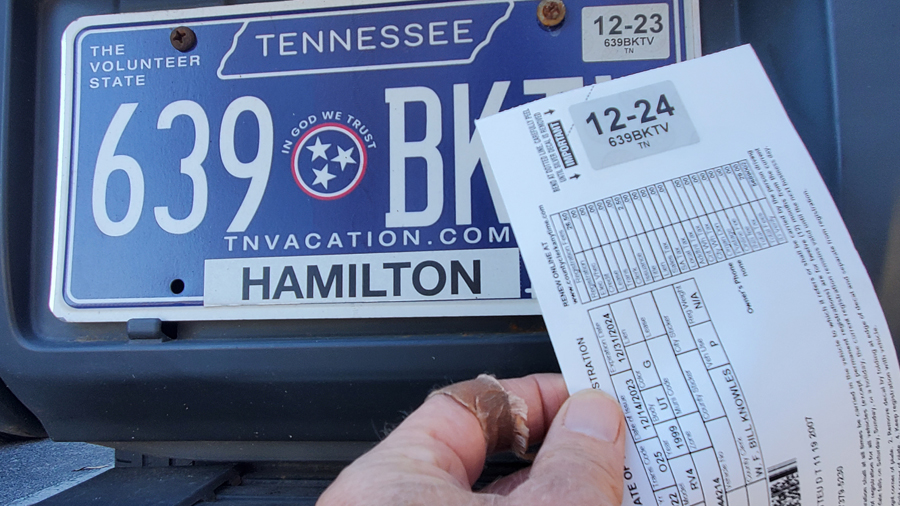

I renew for a year the tag on my RAV4, one of two old cars I use on the public streets. This car, figuring in my false arrest Nov. 22, is registered with the department of revenue so I can use ot for commercial purposes. Separately, I am fighting to regain registration on my 2000 Honda Odyssey minivan, which is no longer a motor vehicle, but a mere automobile, having had its tag revoked for lack of a motor vehicle insurance policy. I claim the law does not require insurance, but only proof of financial responsibility after a qualifying accident. (Photo David Tulis)

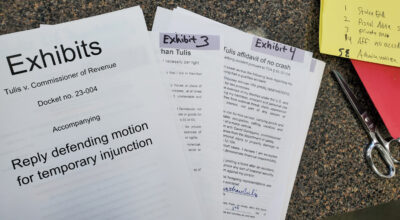

CHATTANOOGA, Tenn., Saturday, Dec. 16, 2023 — On Wednesday I filed with the AHO, the administrative hearing officer, my reply brief making crystal clear that Cmsr. David Gerregano is running a rogue enforcement operation as part of regulatory capture in state of Tennessee. The state is captive of the insurance industry, and Gerregano is to be thanked for giving corporate players at least F$1 billion in extra premium proceeds a year.

He does so by enforcing the Tennessee financial responsibility act of 1977 promiscuously upon all registered vehicle owners in violation of the law. The law says he spot violators only among the special category of “high risk” drivers who have violated the TFRL in a previous accident, having failed to show financial responsibility in dealing with its consequences.

In asking for a temporary restoration of my tag while the case is in progress, I must show irreparable harm and likelihood of success, two of four standards I must meet to win relief by injunction.

This post is the argument portion of my reply to the commissioner, represented by his top staff attorney, Camille Cline.

The EIVS system is intended by the legislature to be a continuing monitoring method for those owners, drivers and operators who have shown financial irresponsibility or who are under state supervision for three years or five years as a condition for a license.

It is intended to make sure that a high-risk man or woman doesn’t fail to keep up his or her part of a bargain: Get your privilege restored — and keep it on condition of buying a high-risk motor vehicle insurance policy. Don’t drop coverage or you’ll lose the privilege. EIVS makes the net escape proof against these subjects. That is its scope in the interest of public health, safety, welfare and revenue. The Atwood EIVS system is not intended to target every user of a registered car. It is not intended to criminalize people, starting with the poor, who often cannot afford insurance and have been victimized by this official fraud for at least six years.

The commissioner’s pleadings will work before the court if the Tennessee financial responsibility law of 1977 is made not to work — if its interlocking provisions are delinked, separated or atomized into free-standing units reconstituted by the commissioner for purposes arbitrary and capricious. The department’s arguments are built upon a chaotic and deconstructed set of provisions tyrannical and oppressive upon petitioner violating the rule that if there is any uncertainty as to whether a power exists versus the right of the citizen, the claim of the citizen prevails.

The rule of lenity is that ambiguity in a statute defining a crime or imposing a penalty should be resolved in the citizen’s favor. “[C]onduct proscribed must be defined specifically so that the person or persons affected remain secure and unrestrained in their rights to engage in activities not encompassed by the legislation. Blurred signposts to criminality will not suffice to create it.” United States v. Cong. of Indus. Organizations, 335 U.S. 106, 142, 68 S. Ct. 1349, 1367, 92 L. Ed. 1849 (1948).

Puzzle pieces don’t fit

In this case, there is no real uncertainty about the law and its meaning and application, and those parties subject to performance under it. Every puzzle piece touches every other other puzzle piece and all the edges fit together with no gaps, as petitioner explains it. They cohere. Mr. Gerregano’s puzzle pieces in sect. 139 and Atwood are supposed to fit into contours of other puzzle pieces – such as Part 1. But they don’t, his response indicates. He trims pieces off or forces them together on mystical grounds that his “administration of the Atwood Law gives effect to the General Assembly’s objectives” to boost rates of insured autos (response p. 13). The legislature and the commissioner believe shortcuts work. But they don’t when members of the public are harmed. If the general assembly wants compulsory insurance, it has to junk the existing law and pass a rewrite. It rejects in 1999 the Stulce bill that simply tacks on the “mandatory insurance” duty with no rescission of all mooted parts. If the general assembly wants what DOR alleges it wants, it cannot take a former dentist’s office building, as it were, and convert it into a residential duplex simply by changing the door of a backyard storage shed. The structure must be completely rehabbed.

The commissioner’s legerdemain in creating revenue authority from his arbitrary and capricious will appears in the attack on the key fact in this case – that being the absence of a qualifying accident or judgment. EXHIBIT No. 4 Affidavit of no accident.

The commissioner says,

The fact that Tenn. Code Ann. § 55-12-105(a) directs DSHS to request that the Department suspend registrations in connection with post-accident reporting does not foreclose the subsequent creation of an entirely separate enforcement mechanism for financial responsibility requirements via the procedures established by the Atwood Law. Both things are true—the Department is directed to suspend registrations for failure to comply with financial responsibility requirements post-accident at the request of DSHS and by the Atwood Law where insurance coverage cannot be verified and the registrant fails to show other proof of financial responsibility or otherwise cure noncompliance.

Response p. 5

No authority from legislature

The “subsequent creation” of an “entirely separate enforcement mechanism” greased by technological upgrades bringing unity of purpose among regulator and related for-profit insurance corporations. This “separate *** mechanism” is without authority from the general assembly.

Prattling on, the commissioner cites sect. 210 that authorizes DOR “to initiate its notice procedures ‘if there is evidence … that a motor vehicle is not ensured’” (emphasis added in original), and that had it not intended revenue to create an entirely separate mechanism, “it could have easily done so.”

The general assembly easily does so with a 14-word red-flag roadblock in Atwood:

Nothing in this part shall alter the existing financial responsibility requirements in this chapter.

T.C.A. § 55-12-214. Financial responsibility requirements unaffected

The department next says, “[T]he lack of any qualifying or narrowing language leaves the EIVS inquiry open to any motor vehicle registered in Tennessee” response p. 6. The commissioner asks the hearing officer to believe that Part 1 of the law, sects. 101 to 143, is not “qualifying or narrowing” to the Atwood verification program.

F$65,000 extortion demand

DOR imposes a $65,000 requirement on poor and impoverished people effectively requiring them to stay home if they refuse to be coerced into doing business with an insurance company. Under DOR’s arbitrary and capricious practice defied by this lawsuit, a person is denied right of ingress and egress privately — under threat of arrest by cops abrogating constitutionally secured rights — if he does not enter into business with insurance companies, cough up $65,000 cash or purchase a $65,000 surety bond from an insurance company (if available) prior to a qualifying accident as defined by the general assembly.

This case deals with a state privilege. Financial solvency requirements COULD be imposed on all privileged applicants, but it would be a new tax and would have to be paid universally by all, from gran’mas to beefy 18-wheeler drivers, and it would have to be imposed by the legislature. DOR policy legislates this goal in breach of the constitutional division of powers. That the statute allows no hearing over TFLR in the department in a denial of due process shows what happens when violation begets violation. Properly applied, the law gives petitioner a hearing before suspension, which originates in safety, the moving party in every license revocation.

The law makes Tennessee an after-accident voluntary insurance financial responsibility state, as court cases show. Under the commissioner, Tennessee is pre-accident financial solvency mandatory insurance state with a total ban imposed upon the driving privilege upon condition.

Choose your posion

Mr. Gerregano lets petitioner decide which abuse best suits. (1) Buy a motor vehicle insurance policy he is too poor to buy, or (2) send the commissioner of safety a $65,000 check (even more unlikely), or (3) buy a $65,000 surety bond to guarantee payment of a future $2,000 fender bender or somesuch mishap (costly, difficult or impossible to obtain), or (4) face criminal arrest under policy for using the disputed minivan as a private automobile, because agents of state of Tennessee deny the very existence of the right of ingress and egress and the commissioner refuses to address the issue in his response. EXHIBIT No. 5 Administrative notice; affidavit on right of ingress, egress from abode, land in Tennessee.

Given the constraints of the law it is specious to say that the arrest threat from local deputies and police is caused by petitioner as he “elects to drive on a suspended registration” and that arrest injury is “speculative” and “voluntary,” response p. 12. Because he uses his car of necessity and for enjoyment of God-given rights, he is bringing arrest upon himself in use of his property, an “avoidable injury.”

Petitioner puts the hearing officer on administrative notice of his and the people’s ingress and egress rights connecting them to the soil and to their houses, dwellings, homes, habitants or residences. The highways belong to the public; the state is trustee. There appears no recognition of this fundamental distinction by the commissioner.

By rejecting any conception of private travel, DOR is denying it has capacity or willingness to see the sharp white line separating travel and transportation. DOR refuses to see distinction between taxable and nontaxable activity, between public and private, regulable and free, state and people. In bullying against ingress and egress (travel) rights, it likewise shows a heart and mind willing to infringe against people’s rights under Tennessee financial responsibility law of 1977. CUSTOM, USAGE AND ABUSAGE control administration of TRFL under a commissioner who rejects clear duty under well known law.

‘Restrict unlawfully another’s freedom of action’

The acts against petitioner are in violation of the felony statute at § 39-14-112. Extortion, which states, “A person commits extortion who uses coercion upon another person with the intent to: (1) Obtain property, services, any advantage or immunity; (2) Restrict unlawfully another’s freedom of action; or (3) (A) Impair any entity, from the free exercise or enjoyment of any right or privilege secured by the Constitution of Tennessee, the United States Constitution or the laws of the state, in an effort to obtain something of value for any entity. *** ” DOR and its law enforcement cohorts are restricting petitioner’s “freedom of action” in ingress and egress rights, and many others, using coercion upon him to obtain “property, services, any advantage or immunity” which substance is not immediately in purview of this suit.

The commissioner is “making it up” as he goes, in fraud, violence and public injury, among other harms alleged of record and under administrative notice. Until the time this matter is fully briefed, orally argued and decided, petitioner has a clear right to injunctive relief, and asks the hearing officer to give it.

Relief requested

Petitioner demands the following:

- That in considering a temporary injunction, the hearing officer account for the affidavit of no accident, and that he view this evidence as likely to be dispositive in this case;

- That in light of this fact, the judge will begin to apply the law properly to this fact and discern that he will likely find the revocation illegal;

- A temporary tag pending resolution of proceedings, lasting until the last day after which the appeal period expires;

- A finding of law and fact as to the department’s authority to regulate commerce on the roads, as distinct from that free area of Tennessee’s great and powerful open market economy where the department has no authority to operate, and whether it is likely that this finding will prove in favor of petitioner’s claims regarding his foundational ingress/egress rights upon which piggyback his rights in commerce under privilege of his motor vehicle registration with the department of revenue.