Chief judge of the 6th circuit court of appeals Jeff Sutton is being asked to review the federal courts’ use of state law to determine how long people have to file lawsuits. (Photo news.uni.edu)

The rules controlling among the states how soon a plaintiff must file a 42 U.S.C. § 1983 action such as David Jonathan Tulis v. William Orange et al are arbitrary and capricious, giving a citizen in one state a year to file suit, while if he lives in another state he gets two years — or more.

By David Tulis / NoogaRadio Network

[This essay is a supplemental filing in my lawsuit against Tennessee supreme court justice Roger page, policeman William Orange and others to force judicial conferences to be open to the public and to enforce the constitutional protections for the right to be arrested under a warrant. The case is on appeal in the U.S. 6th circuit on grounds of untimely filing. I argue that the lawsuit for relief and equity is not untimely filed, and here argue that the practice of setting filing deadlines based on state statutes of limitations are uneven and ultimately unjust. As far as we know, this challenge is without precedent. — DJT].]

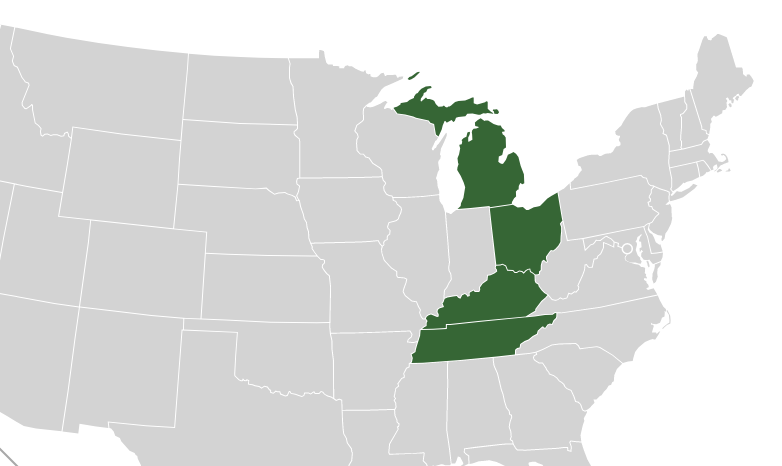

This map puts Tennessee in the U.S. 6th circuit court of appeals. Some states give two years to file civil rights suits like mine. One state allows three years. I am trying to keep my suit alive by pointing out that a uniform standard must exist among these states for filing of suits.

The hopscotch level of protection among the states, and the federally protected citizens in them, does not comport with the equal protection clause of the 5th amendment to the U.S. constitution that “No person shall be *** deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law,” which due process is guaranteed to all U.S. citizens equally under the 14th amendment, “All persons born or naturalized in the United States *** are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside. No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States; nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law; nor deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.”

Section 1983 does NOT provide a statute of limitations. Federal courts are directed to follow the most analogous state statute of limitations pertaining to injuries to the rights of a person in sect. 1988. Wilson v. Garcia, 471 U.S. 261 (1985). The court has had trouble determining which limitation deadline to follow for residents in a given state if there are several afforded, depending on the tort alleged by the party living in his state. But as among the states in a given appellate circuit, inconsistency persists.

The spread in the 6th circuit is great. Kentucky and Tennessee have a year in which to sue for damages. Ohio has two. Michigan has three years.

Why does a U.S. citizen falling within the territorial jurisdiction of U.S. district court sitting atop the soil of Illinois and Ohio enjoy twice (x2) the allotted time than in Tennessee in which to file a § 1983 claim? Why is U.S. citizen domiciled in the territorial jurisdiction of a U.S. district court belonging to the same sovereign government (but situated atop the soil of some other state) is disproportionately benefited or prejudiced by an unequal “statute of limitations” due process standard by which to file an identical §1983 claim?

Chris Sapp, right, is a legal activist and savvy reader of the law, the midstate bureau chief of NoogaRadio 96.9 FM. This analysis is largely his work. (Photo David Tulis)

Are we to understand that a U.S. citizen in the territorial jurisdiction of federal courts in the 1st circuit (Maine) enjoys six times (x6) the protection of federal courts under the U.S. constitution as a similarly situated citizen with an identical civil rights claim domiciled in the 6th circuit, equally seeking vindication of his “‘federal rights elsewhere conferred’” Graham v. Connor, 490 U.S. 386, 393 (1989) (quoting Baker v. McCollan, 443 U.S. 137, 144 n.3 (1979))?

Are we to believe that some animals really are “more equal” than other animals with regard to their civil rights claims!?

Analysis

Since federal rights secured by the 1st, 9th, and 10th amendments of one sovereign government are violated within the overlapping territorial jurisdiction of another sovereign government, any equal protection claim for due process demanded from the federal courts would arise under the 5th amendment (federal) rather than the 14th Amendment (state).

Sect. 1988 specifies that if a case to vindicate rights encounters an insufficiency in federal protective statutes, law in the state where the federal court sits controls “so far as the same is not inconsistent with the Constitution and laws of the United States.”

The due process U.S. citizens receive for the vindication of federal rights claimed in one U.S. district court differs widely from the protections others receive, or that they would otherwise receive themselves, if filed in a U.S. district court elsewhere within the same territorial jurisdiction of the same sovereign government.

It is unjust for Franklin, Tenn., cop William Orange, if he lived in Maine and were involved in an abuse of a citizen, to have to wait six years to be sued by an offended party like me. In Tennessee, he has to wait only one year to see if a harm generates litigation in federal court — a length of time I argue is unfairly short to me, given variations in filing deadlines in other states.

This disparity in treatment occurs because 42 U.S.C. § 1983 fails to establish a federal statute of limitations standard for filing and processing of § 1983 claims occurring to U.S. citizens residing within its own sovereign territorial boundaries. Consequently, the U.S. courts “[inconsistently] with the Constitution” misapply state due process/statute of limitations standards used for processing state civil tort claims properly arising in the state, and differing from state to state under the 14th amendment if filed in the courthouses of those sovereign entities.

Resultantly, U.S. citizens such as appellant are unconstitutionally denied and deprived of equal federal due process protections they should otherwise uniformly receive for the vindication of their federal rights violations following the accrual of a § 1983 claims arising within the territorial jurisdiction of U.S. federal courts.

Tennessee and Ohio are foreign to the United States, the courts of which are like embassies. U.S. embassies in foreign lands are on American soil, their authority representing the laws and interests of the United States alike among them. People in Mexico City or Istanbul enter an embassy each like the other. The diverse law bodies in Mexico or Turkey don’t control the rules or law of the embassy nor its sponsor.

Ohio and Tennessee laws should not control U.S. filing limitations, especially when appellant is severely disadvantaged over a complainant in Ohio.

The U.S. government is a separate and distinct sovereign from that of each of the 50 sovereign states, ipso facto, the federal courts must apply one uniform standard of equal protection and due process when vindicating the federal rights of its citizenry, which may differ widely from the due process statute of limitations considerations provided to citizens of the 50 states when vindicating state civil tort claims originating within the territorial jurisdiction of their sovereign courts.

A fortiori, the current directive guidance governing statute of limitations deadlines for filing § 1983 claims in the various U.S. district courts, as today applied, is a clear and unequivocal abrogation or enlargement of due process guarantees “equally protected” and afforded each U.S. citizen. Such determinations improperly vary and shift from courthouse to courthouse (even within the same federal circuit) based on the presumptive, but incorrect, application of state-specific due process standards, arising under the 14th Amendment, which differ widely from one sovereign state to the next.

In Maine, police officers such as William Orange face lawsuits six years after the alleged offense. That duration lets plaintiff sit on his rights, and the case grow stale, and appears unjust to state actor defendants such as Officer Orange. In Tennessee, the protections appear as great as can be to a defendant, and unjust to plaintiff by comparison to other states.

Such divergence can’t happen without it being a violation of 5th Amendment due process guarantees “equally protected” and afforded to each U.S. citizen uniformly.

Relief requested

Appellant asks the court to review this uneven treatment and establish a rule setting, expanding or contracting the statute of limitations so that limitations on civil rights lawsuits uniformly protect all U.S. citizens alike in every federal courthouse.