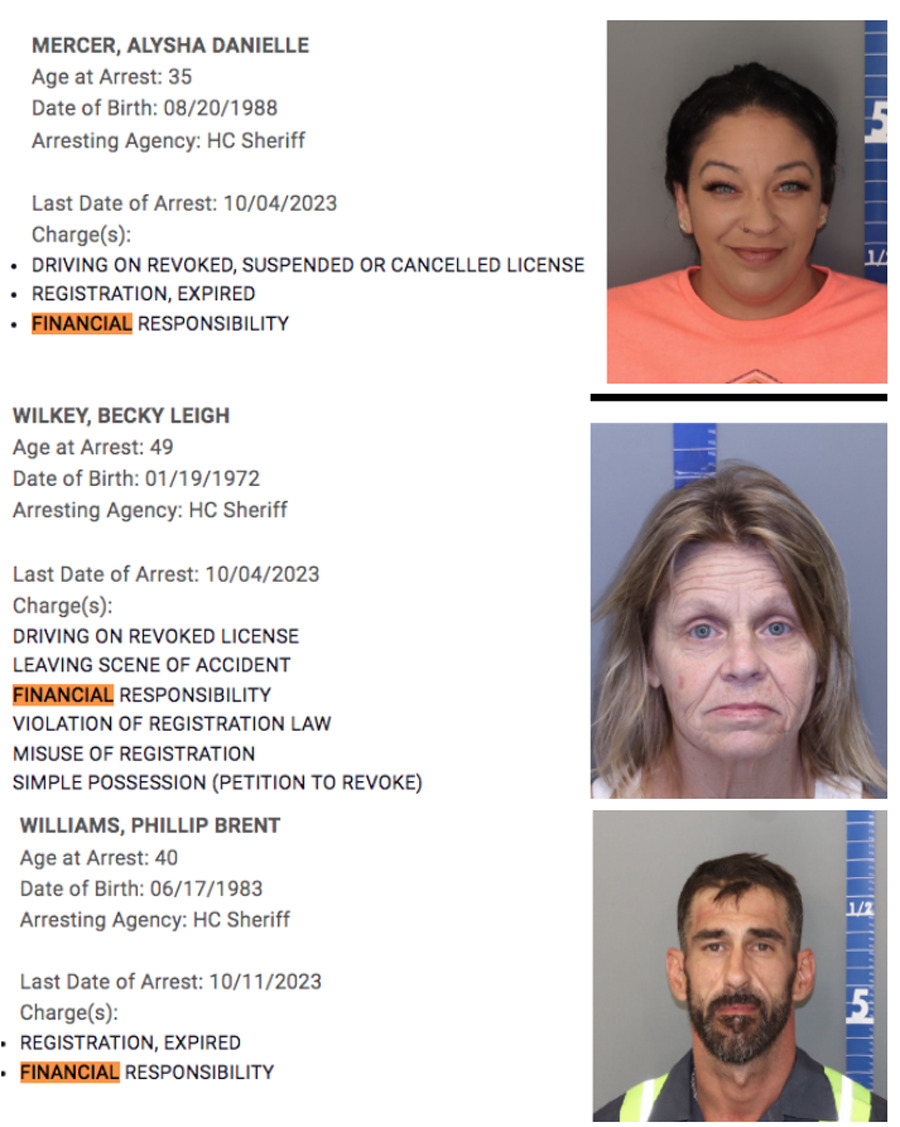

These people are arrested and taken to Silverdale detention center in Chattanooga on charges that they don’t have insurance as drivers or operators of motor vehicles. The charges are entirely bogus and criminal acts themselves because the TFRA (the Tennessee financial responsibility act) does not make us a compulsory insurance state. (Photo from Chattanoogan.com “arrested” report)

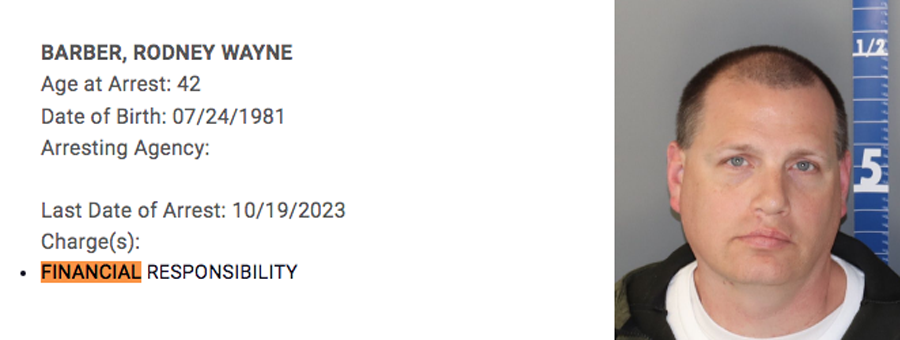

Troopers and other so-called law enforcers abuse the traveling public with arrest, seizure and criminal charges who have not violated the Tennessee financial responsibility act of 1977. (Photo department of safety)

CHATTANOOGA, Tenn., Friday, Oct. 20, 2023 – My fight to remove Brad Buchanan as hearing officer in your case enters a second phase after he rules in an 18-page order that he will not step aside and that he will hear Tulis v. Department of Revenue.

By David Tulis / NoogaRadio Network

I’m suing to overturn a fraud and an oppression by a network of official misconduct actors in the department of revenue, with approval and complicity of the governor, the main political parties and the legislature and judiciary.

The second phase in the gateway fistfight is demanding reconsideration of his order and preparing to sue interlocutory (suit within a suit) to get a chancery court order compelling him to step aside.

Rodney Wayne Barger is seized and arrested on the sole charge of violating T.C.A. § 55-12-139, which law does not view “traveling without insurance” as a crime. The law is applicable only on people who have been adjudged guilty of a car crash or those who are subject to suspension for previous failure to comply with the TFRA. (Photo Chattanoogan.com)

The larger conflict is over Cmsr. David Gerregano issue is that the commissioner and his cohorts have turned our financial responsibility law, passed initially in 1949 and updated in 1977, into a mandatory insurance scheme supporting the insurance industry and oppressing the weak, the poor, the alien and stranger, and those who don’t want to “volunteer” into a contract with corporate insurance.

In the past five years Mr. Gerregano nd his allies, privies and assigns in city police departments have obtained 408,800 criminal convictions of people “driving without insurance.” This is a fraud about a 20th as bad as the Covid-19 fraud by Gov. Lee, but a major scandal still. I am determined to overthrow clear breach of T.C.A. § 55-12-139 and other parts of the statute. The harm is under color of law, in breach of oath and terms of employment, violative of the state’s official oppression and official misconduct laws. I have put state officials under administrative notice about the law’s requirements.

Standards that apply in agency lawsuits?

Which standard applies in my efforts to recuse Mr. Buchanan? The judicial standard at Rule 10 from the supreme court? Or a lower administrative actor standard that is far, far short of the pristine rule from the top court?

The hearing officer is pretending to travel the high road of judicial partiality regulation while taking the low road of administrative action and maintaining control of the case.

Mr. Buchanan’s shifting of the standard from judicial to a narrow and impliedly lower administrative law standard upon himself (a tougher standard for petitioner) mistakes the general principle of impartiality in view in Jones as applied to a civil asset forfeiture case in which appellant insists sheriff deputies’ seizure of $45,986 of cash benefits the commissioner of safety. “Forfeited property seized by a state agency is sold at a public sale by the Commissioner of General Services, and the proceeds of the sale are deposited in the state treasury subject to being allocated back to the Department of Safety to be used to enforce the laws regulating narcotic drugs and marijuana. The Department of Safety does not have access to the proceeds from the sale of property seized by the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation or local law enforcement agencies.” Jones at 825. Judicial ethics rules applying narrowly to facts in the cited case need not limit this petitioner’s demand for full protection under the broad judicial standard highlighting “the appearance of impropriety.”

Mr. Buchanan says if the commissioner can hear a case, then any assignee of the commissioner can hear the case with equal impartiality, and therein elude the judicial standard invoked by petitioner. If this is true structurally in agency proceedings, Mr. Buchanan is witnessed in his order as denying due process structurally, in the design of the administrative state secured in the act at Tennessee code Title 4, chapter 5.

In his denial of recusal order, Mr. Buchanan addresses a matter raised by the commissioner before having received my timely filed answers.

Mr. Buchanan defends himself on the “direct, personal pecuniary interest in the outcome” standard as if this one area of possible bias invoked in Jones covers him from petitioner’s broad rebuke of bias and prejudice under Canon 1 Rule 1.2 of his need to avoid impropriety and “the appearance of impropriety.” He says petitioner is making a structural absolutist argument in the opposite direction from his own totalistic position — that no assignee of an executive branch commissioner can be a neutral judge in a contested case under the judicial standard in Rule 10.

Arising before the court is the insoluble problem of quasi-judicial proceedings in the administrative state intending to not overthrow appearances of operating under the constitution in ostensible benefit of a free people. How can an executive agency perform a judicial function, required by reason and under law to be neutral, nonpartisan? Petitioner is under pressure to signal his suspicion that the entire pre- or sub-judicial adjudication process in agency is unconstitutional, with the only possible just adjudication being by a real judge under art. VI, judicial department, able to deliver justice in instant cause. The courts are scarcely willing or ready to take on agency caseload if UAPA contested case hearings were somehow abolished and limited constitutional elected and democratic government restored. No, Tennessee government under the remedial legislation of UAPA intends for agencies to handle conflicts internal to their expertise and jurisdiction first, as an economy and a reasonable outworking of the doctrine of subsidiarity, with judicial review of the record following. Is such an arrangement inherently unworkable or monarchial absolutism, as Columbia University prof. Phillip Hamburger suggests in Is Administrative Law Unlawful? (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014, 648pp)? The Tennessee supreme court is increasingly less concerned about appearance of bias in administrative venues.

Though petitioner has rights guaranteed under the U.S. const. 14th amendment to due process and equal protection, and is aggrieved by agency prosecution of him (by Cmsr. Gerregano) against his privilege (vehicle registration), he will suppress his desire to attack the whole of the administrative state as a coup against constitutional government and instead reiterate his demand for relief limited to his case: To be treated fairly in agency by process as closely aligned as possible to the Tennessee constitution to get treatment as close as possible to that from a truly neutral judge in a Tennessee circuit or chancery court.

Filings over this matter show two extremes. (1) The AHO defends himself by saying the commissioner-tapped AHO can judge because the commissioner himself by law can sit and hear the case. Conversely, (2) the petitioner defends his cause citing T.C.A. § 4-5-303(b) (“A person who is subject to the authority, direction or discretion of one who has served as *** prosecutor *** in a contested case may not serve as an administrative judge *** in the same proceeding”) and the “appearance of impropriety” forbidden under Canon 1 Rule 1.2 (which standard could theoretically ban any Gerregano employee from hearing a contested case if said issue is properly raised).

The UAPA provides a way to break deadlock.

That is the secretary of state’s administrative procedures division headed by Stephanie Shackleford handling 8,100 hearings, mediations, and prehearing conferences a year for cities, counties and agencies state and local. By an honorable turning of this relief valve, controversy over the hearing officer is amicably settled. Cmsr. Gerregano can be confident his substitute agent hearing the case will be fair to him and to the law, and petitioner will be sure the alternative hearing officer will give his claims about law and fact a fair shake.

I believe Mr. Buchanan will not recuse, and I believe he will refuse my notice to depose Mr. Gerregano. That means interlocutory appeal to Davidson County chancery, venue for all appeals for “judicial review” out of an agency contested case.