NASHVILLE, Nov. 29, 2022 — Children taken into the custody of the Department of Children’s Services are spending upwards of eight months in hospital beds across Tennessee because the agency says it has nowhere else to put them.

By Anita Wadhwani / Tennessee Lookout

The children typically land in DCS custody after being removed from homes on allegations of abuse or neglect and often carry the dual weight of trauma from their home life—and their sudden removal. The responsibility of DCS, which has a budget of more than $1 billion annually to carry out its mission, is to protect and care for these children.

Instead, DCS officials acknowledge, children are being unnecessarily hospitalized for periods of time that have ranged this year from one day to 264 days.

Gov. Bill Lee recently said “It’s important that we in particular provide a level of transparency to all of these processes,” yet his spokesperson did not respond to a request for comment, DCS Commissioner Margie Quin declined a request for an interview and a staff lawyer for DCS has failed to provide the total number of children in state custody being housed in hospitals.

Some of the hospitalized children have tracheostomies. Others are older children in wheelchairs. There are also kids with both medical and behavioral health needs that don’t rise to the level of requiring inpatient hospital care, according to information provided by John Waddell, senior associate counsel at DCS.

The practice of hospitalizing kids—for the length of an entire school year, in some instances—when they do not require hospital care is a violation of the Americans with Disability Act, a federal law guaranteeing people with disabilities the right to live in the least restrictive environment possible, said Michele Johnson, executive director of the legal advocacy organization, the Tennessee Justice Center.

“It definitely violates the ADA to put kids in hospitals who don’t need to be there just because they (DCS) can’t get their act together,” Johnson said. “You cannot put a child in a hospital when their medical needs don’t require it. We do not institutionalize kids based on their disability. It’s harmful and damaging to kids.”

Waddell said that “anyone who is taken in custody by the state has an expectation of a certain level of care. In the case of children, the department makes its decision based on what is in the best interest of the child and what options are available at that time.”

’Disruptive’ youth hospitalized

For more than a year, DCS has come under public scrutiny as reports emerged of children sleeping on the floors of state office buildings. Social workers have spoken up about crushingly high caseloads.

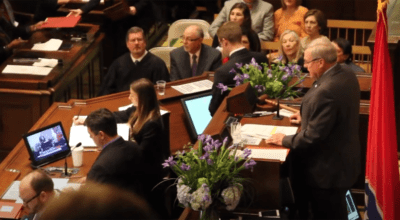

And during a budget hearing earlier this month, incoming DCS Commissioner Margie Quin laid before Gov. Bill Lee a confluence of factors that she said she is trying to address in her third month on the job.

Among them: while there are enough beds in privately operated residential treatment facilities for kids with specific behavioral or medical needs in DCS custody, the agency can’t pay their rates. Many of those beds go to children from out of state, or those whose families or insurance companies can afford to pay for treatment.

Quin described a “pretty horrific turnover rate” among social workers, deterred by low pay, high caseloads and increasingly stressful working conditions. Nearly half of starting caseworkers leave in their first year on the job, she said. The state is seeing record numbers of children in DCS custody.

And, she said, children in DCS custody who become too “disruptive” when forced to sleep in offices are among those sent to hospitals.

“It definitely violates the ADA to put kids in hospitals who don’t need to be there just because they (DCS) can’t get their act together. . . We do not institutionalize kids based on their disability.”

– Michele Johnson, Tennessee Justice Center

Quin is seeking a $156 million boost in the agency’s $1.1 billion budget, a request to which Lee appeared receptive.

“I would encourage us to move forward aggressively,” Lee said during the Nov. 17 budget hearing. Lee also urged DCS officials to be open about the problems they face.

“It’s important that we in particular provide a level of transparency to all of these processes going forward,” Lee said. “We should all know, and everyone should know, when we see a problem and we need to fix it, we are going to do that but understanding that everyone should have eyes on that fix, because this population is really important to all of us and we need to make sure we do it right.”

A spokeswoman for Lee did not respond to a request for comment about the hospitalizations, and Quin declined the Lookout’s request for an interview.

Earlier this month, Waddell – the DCS attorney – said he was in the process of gathering information on the total number of kids needlessly hospitalized this year. He has yet to provide that data to the Lookout.

Democrats urge immediate action

Quin’s budget request is for next year, but some Democrats have urged the governor to take action now to keep children from sleeping on office floors and hospitals beds.

In a Nov. 21 letter to Lee, 11 Democratic state lawmakers said children are dying and suffering additional trauma due to the staffing crisis and that solutions should not be put off until the next budget year, which begins in July 2023.

“While an increase in funding next year is certainly necessary, something must be done to address the DCS emergency in the interim,” the letter said.

“The opportunity costs and externalities alone—with increased hospitalization, mental health, and criminal justice demands—over the next seven months seem inadvisable even if we look at this purely from a financial perspective,” the letter said.

Lee has not yet publicly responded.

In hospitals, alone, accompanied

Instead of overall numbers of kids placed in hospitals this year, Waddell provided a snapshot of the number of kids in hospitals as of Nov. 18, leading into the Thanksgiving holidays.

Twelve children were hospitalized due to a lack of suitable placements, according to Waddell. Ten were placed in children’s hospitals and two were at other, unspecified types of hospitals.

All but two had medical conditions “that are making placement hard,” Waddell said.

“Children who have tracheostomies are harder to place, especially with the current shortage of home nursing,” Waddell said via email.

“Older children in wheelchairs can be hard to place also, and the hardest ones are those with both medical and behavioral/mental health needs,” he said. “Many children with simpler medical needs find placement within a day or two.”

Children forced to stay in hospitals are sometimes accompanied – and sometimes they are alone, he said.

“It depends on the child’s needs,” Waddell said. “Some children have a DCS worker or contract provider worker with them at all times, some have a sitter (hired by DCS or by the hospital), and some have no one there full time. For some, parents are visiting also. The DCS case manager and DCS regional health nurse monitor the child’s condition very frequently and are in constant communication with hospital staff.”

Waddell also described varying levels of access to education for the children placed in hospitals.

Children first need to be cleared by a medical team to receive education services, he said. The child’s school is responsible for educational services while in the hospital; if there is no school on record, DCS would provide remote learning, and pay for a sitter or tutor to provide extra in-person assistance if needed.

Children with individualized educational plans, which provide accommodations that can include therapy and tutoring, are likewise the responsibility of their local school officials, he said. If the child has no school of record, DCS would be irresponsible.

“If DCS is responsible, we would be able to meet most services through remote learning,” he said. “It would be based on [the] child’s needs and IEP. If additional services were needed, we would work with the hospital as well to bring in vendors.”

‘Sparkly unicorn’ of care for wheelchair-bound

Emily Jenkins, a Franklin-based attorney who serves as an advocate for children experiencing abuse and neglect, said that the description of wheelchair-bound older children left in hospitals did not come as a surprise.

“It is difficult enough to find an appropriate placement for healthy kids,” said Jenkins, “Teenagers in general are hard to place. Trying to find someone physically capable, having a handicapped accessible bedroom, which would be on a first floor, is like a sparkly unicorn.”

Jenkins, who serves as vice president and interim board president for CASA, an organization of court appointed advocates for children, said the responsibility for addressing crises within the state’s child welfare system should be shared widely.

“I think when we look at these issues, it’s far too easy to sum them up as a failure to try,” she said. “It’s a bigger responsibility. We need everyone in the state, including the legislature to pony up money and make policy changes.”