Motorcyclists with the Hamilton County sheriff’s department roar up a hill. (Photo HCSO)

Sheriff Austin Garrett, whom I am suing personally and officially for false arrest, puts a sticker on a child’s chest during a downtown Chattanooga parade. Sheriff Garrett illicitly uses criminal authority to administer the motor vehicle privilege, which is subject to the doctrine of the exhaustion of administrative remedies on the part of the movant state of Tennessee in any traffic case, my suit says. (Photo HCSO)

CHATTANOOGA, Tenn. Saturday, Aug. 9, 2025 — My lawsuit against deputy sheriff Brandon Bennett, his boss sheriff Austin Garrett and Hamilton County, Tenn., for false imprisonment and false arrest is premised on privilege.

Arrest over a damaged auto taillight is, they alleged in criminal proceedings, a crime. My answer has been: No it’s not. At best, as upon any licensee (person with license, or presumed to be a licensee), it’s an administrative infraction suitable for a contested case in the Tennessee department of safety.

I was arrested Nov. 22, 2023, for a damaged taillight and refusing to show a driver license and, effectively, to admit myself into commercial activity in privilege by showing that document when it wasn’t true that I was involved in the activity subject to that document.

Mr. Bennett arrested me. I am suing him for damages and injunction.

My grounds to shake the entire police-industrial complex infrastructure are that privilege law has clear due process requirements subject to the commissioner of safety.

I argue that “driving and operating a motor vehicle constitute a privilege,” just as plumbing, accounting, embalming or scrap metal dealing in Tennessee are privileged. They are state-owned regulable and taxable activities. A privilege is subject to its own commission, all 44 of them in Tennessee occupation code subject to UAPA, the uniform administrative procedures act.

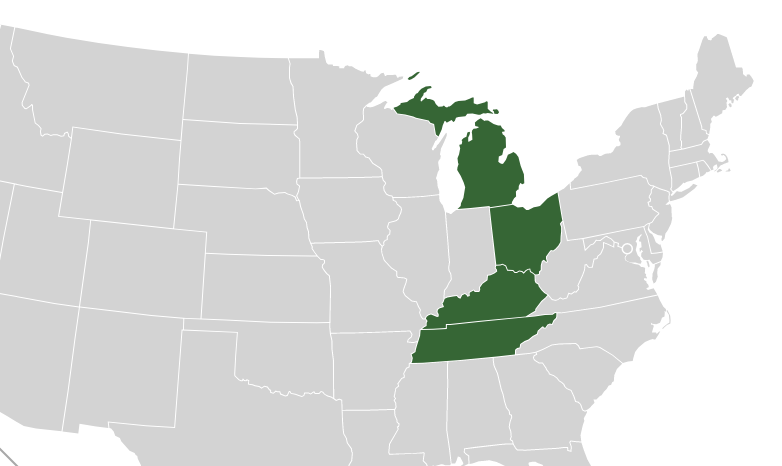

I take pains to clarify this situation for the judges of the U.S. 6th circuit court of appeals. Excerpts. (Footnotes are in the large type.)

This is the federal 6th circuit appellate district.

***

Petitioner accounts for Tennessee privilege law, regulation of motor vehicles, the distinction between privilege taxable activity and private travel, controversies under motor vehicle regulation and the probable cause standard for criminal enforcement. This suit challenges the lower court’s refusal to account for this coherent system of law.

Privilege is upon for-profit activity

ISSUE — Whether government grants, certificates or licenses can be reliably understood as requiring due process laid out by authorizing parties in law.

Complaint is premised on the legal fact that driving a motor vehicle is a privilege that has commerce as an essential element.

TAXABLE ACTIVITY

“The license tax is one imposed on the privilege of exercising certain businesses, callings, professions, or vocations. 17 R.C.L. 475, Sec. 2. It is not imposed on the ownership of the business, or a sale of it, or of the good-will incident to it, or an agreement not to exercise the privilege of doing it. ‘The essential element of the definition of privilege is occupation and business, and not the ownership simply of property, or its possession or keeping it. The tax is on the occupation, business, pursuit, vocation, or calling, it being one in which a profit is supposed to be derived by its exercise from the general public, and not a tax on the property itself, or the mere ownership of it.’ Phillips v. Lewis, 3 Shan.Cas. [230], 231”. 10 Michie’s Digest of Tenn.Reports, 2nd Ed. 522–523, Section 3. Draughon v. Fox-Pelletier Corp., 174 Tenn. 457, 126 S.W.2d 329, 333 (1939). “‘Privileges are special rights, belonging to the individual or class, and not to the mass; properly, an exemption from some general burden, obligation or duty; a right peculiar to some individual or body.’ Lonas v. State, 50 Tenn. 287, 307” Jack Cole Co. v. MacFarland, 206 Tenn. 694, 337 S.W.2d 453

“To operate a motor vehicle on the public highways of this state…… is wholly separate from the right to travel. The ability to drive a motor vehicle on a public highway is not a fundamental ‘right.’ Instead, it is a revocable ‘privilege’ that is granted upon compliance with statutory licensing procedures” (citations omitted) State v. Booher, 978 S.W.2d 953, 957 (Tenn.Crim.App.1997). “It is well settled that ‘the ability to drive a motor vehicle on a public highway is not a fundamental right. Instead, it is a revocable privilege that is granted upon compliance with statutory licensing procedures’” State v. Ferrell, No. M2007-01306- CCA-R3-CD (Tenn.Crim.App. 08/07/2009). “It cannot be denied that the Legislature can name any privilege a taxable privilege and tax it by means other than an income tax, but the Legislature cannot name something to be a taxable privilege unless it is first a privilege. …..’A privilege is whatever business, pursuit, occupation, or vocation, affecting the public, the Legislature chooses to declare and tax as such’” Corn et al. v. Fort, 170 Tenn. 377, 385, 95 S.W.2d 620, 623, 106 A.L.R. 647 (emphasis added).

‘BUSINESS, PURSUIT, OCCUPATION, VOCATION’

The judges of the 6th circuit court of appeals meet here in Cincinnati. (Photo U.S. courts system)

The privilege is not upon property, but taxable activity of carrying goods for hire. “The tax here in suit was not a tax levied upon complainant’s water but was a privilege tax levied upon the business of selling the water” Seven Springs Water Co. v. Kennedy, 299 S.W. 792, 156 Tenn. 1, 4 (Tenn. 1927).

“151. ‘Privilege’ is defined.— A privilege is the exercise of an occupation or business which requires a license from some properly constituted authority, designated by general law and not open to all or any one without such license. Mabry v. Tarver, 1 Hum., 94, 98. *** A privilege is whatever business, pursuit, occupation, or vocation, affecting the public, the legislature chooses to declare and tax as such. Mabry v. Tarver etc.” Constitution of the State of Tennessee Annotated, Robert T. Shannon, 1916, pp. 214, 215.

Appendix in the complaint, and in this petition, explains privilege from the leading case Phillips v. Lewis, Shannon’s Code, Vol. III 230, 240 (1877).

“Merchants, peddlers and privileges” are the defined objects of taxation in the latter clause of the section. It is certain the merchant is not taxed except by reason of his occupation, and in order to follow or pursue this occupation – one of profit – in which it may be generally assumed capital, skill, labor, and talent are the elements of success, and are called into play by its pursuit. This pursuit or occupation is taxed, not as property, but as an occupation..”

(Doc. 1, PageID # 40, emphasis in original) also APPENDIX EX. No. 2

The motor vehicle driving privilege, like all others, is obtained by application. “Every person applying for an original or renewal driver license shall be required to comply with and be issued a classified driver license meeting the following requirements ***.” T.C.A. § 55-50-301. The motor vehicle law applies upon privilege recipients.

Appellant is free in enjoyment of his constitutionally protected property, religion or press rights to use the road for pleasure and private purpose apart from privilege. Truck drivers describe using the road but not participating in privilege taxable activity (private profit and gain) as “dead-heading.” That’s what appellant was doing the hour of his seizure.

TROOPERS’ UNIQUE POWERS

Appellant’s streetside demands for evidence of commerce constituting privilege taxable activity is based on awareness of the duty given to DOSHS officers to obtain evidence of commerce in regulating the privilege. The department administers the motor carrier statute, T.C.A. § 4-3-2012. Its troopers “patrol the state’s highways and enforce all laws, and all rules and regulations of the [U.S.] department of transportation regulating traffic on and the use of those highways” and “assist *** in the collection of all taxes and revenue.” T.C.A. § 4-7-104.

They probe “operators of motor vehicles for hire as they may see fit” to see if the operator is compliant with title 65, chapter 15 T.C.A. § 4-7-105. “This part is necessary to: (1) protect the lives and safety of the traveling public on state highways; (2) conserve and preserve the state’s property” T.C.A. § 4-7-113. The carrier statute recognizes distinction between privileged and non-privileged travel, the law directing troopers to “[p]rotect the welfare and safety of the traveling and shipping public in their use of the highways, and in their contact with the agencies of motor transportation and allied occupations” T.C.A. § 65-15-101 (emphasis added).

A trooper is authorized to demand exhibiting of a driver license without probable cause. T.C.A. § 40-7-103(c). A party exercising the motor vehicle privilege has pre-agreed to supervision as a condition of obtaining the commercial privilege with no probable cause. T.C.A. § 40-7-103(c) (emphasis added) FN 3,4

3 The courts warn against easy misuse of this power. “Without regard, however, to the right of the Highway Patrol Officers to check on the licenses of drivers of foreign licensed cars, the officers must exercise this right to check operators’ licenses in good faith and not as a pretext or subterfuge for an inspection of or a prying into the contents of an automobile or any other possession of a citizen.”

Robertson v. State, 184 Tenn. 277, 198 S.W.2d 633, 635 (1947)

4 Unless a law enforcement officer has probable cause to believe that an offense has been committed, no officer, except members of the Tennessee highway patrol acting pursuant to § 4-7-104, shall have the authority to stop a motor vehicle for the sole purpose of examining or checking the license of the driver of the vehicle.

Defendants criminally charged appellant under the “display on demand” statute T.C.A. § 55-50-351 applicable to a person “operating a motor vehicle.” “Every licensee shall have the licensee’s license in immediate possession at all times when operating a motor vehicle and shall display it upon demand of any officer or agent of the department or any police officer of the state, county or municipality * * *. “ In the Williams Tennessee code annotated 1947, § 2715.21, this authority was exclusively upon “officers of the department,” the state trooper. It was amended to allow municipal officers to impose license inspection authority on motor vehicle operators. APPENDIX EX. No. 16 (see p. 18). “1 Section 8 of Chapter 90 of the Public Acts of 1937 requires that every operator of a motor vehicle shall have in his possession his driver’s license while so operating his vehicle and shall exhibit it upon demand of any State Highway Patrolman. This unrestricted right to demand an exhibition of a license is confined to State Highway Patrolmen. Under this provision these Patrolmen are empowered under the law at any time to stop a car and require an exhibition of the driver’s license.” Cox v. State, 181 Tenn. 344, 347, 181 S.W.2d 338, 339 (1944). FN 5

5 Tennessee supreme court justice Neil adds in a concurring comment, “The exceptional authority conferred upon Highway Patrolmen was due to the fact that their chief duty was to enforce the traffic laws and ordinances in order to promote the safety of the traveling public. The statutes certainly did not contemplate conferring this authority upon them to enable them to circumvent the constitutional provision against searches of the person and property of a citizen without a valid search warrant. If this conviction should be sustained, every Highway Patrolman in the State would at once construe it to mean that he had full authority to search an automobile anywhere and at any time without a search warrant. Such a holding would abrogate the constitutional inhibition against unlawful searches and seizures insofar as it applies to Highway Patrolmen. In order for a search to be lawful, when the Patrolman stops a car to examine a driver’s license, it should be made to appear that the examination is made in good faith and not as a mere blind or an excuse for a failure to procure a valid search warrant.”

Id. Cox at 348 (emphasis added)

Mr. Bennett acts upon the auto taillight owner with no evidence or allegation of evil intent or criminal act, T.C.A. § 39-11-301; without evidence of public disturbance, riot or affray, T.C.A. § 40-7-103; and without a crime victim’s sworn complaint before a magistrate, T.C.A. § 40-6-203.

REASON, MORALITY IN REGULATION

For the general assembly not to regulate and tax commercial use would constitute a taking against the public for the benefit of private business. “The property of the public can no more be taken and appropriated to the use, benefit, and profit of private enterprises, without due process of law and fair compensation, than the property of a private enterprise can be taken by the public without due process of law and fair compensation. Reasonable regulation of transportation companies, operating over public highways, is no more nor less than a valid and reasonable protection against the appropriation of public property by private individuals without due process of law and without compensation” Ex parte Tindall, 1924 OK 669, ¶ 50, 102 Okla. 192, 229 P. 125, 132, 133 (emphasis added).

HIGHWAYS’ TOP USE: ‘PRIVATE PURPOSES’

“These statutes and regulations clearly indicate that the legislature, in enacting the Tennessee Motor Carriers Act, has declared that the public policy of Tennessee includes the protection, safety, and welfare of the traveling public, including those persons who operate motor vehicles regulated by the Act.” Reynolds v. Ozark Motor Lines, Inc., 887 S.W.2d 822, 825 (Tenn. 1994) (emphasis added). “It is well established law that the highways of the state are public property; that their primary and preferred use is for private purposes; and that their use for purposes of gain is special and extraordinary, which, generally at least, the legislature may prohibit or condition as it sees fit.” Stephenson v. Binford, 287 U.S. 251, 264, 53 S. Ct. 181, 184, 77 L. Ed. 288 (1932) (emphasis added).

Troopers, whom the commissioner tells the U.S. department of transportation have “sole agency in the state of Tennessee” to administer the transportation law, protect the general public with monitoring of business operators in trucks, tractors and trailers. FN 6

6 “The Tennessee Highway Patrol of the Tennessee Department of Safety and Homeland Security (TDOSHS) is the sole agency in the State of Tennessee responsible for enforcing laws related to size, weight, and safety regulations for commercial motor vehicles. The Tennessee Highway Patrol is the State’s lead agency for the Motor Carrier Safety Assistance Program and does not fund any sub-grantees.” TENNESSEE Commercial Vehicle Safety Plan Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration’s Motor Carrier Safety Assistance Program Fiscal Years 2022 – 2024 Annual Update FY 2024 Date of Approval: July 30, 2024 (emphasis added)

https://www.fmcsa.dot.gov/sites/fmcsa.dot.gov/files/2024-11/Tennessee%20FY2024%20Final%20CVSP.pdf

DOSHS REGULATES FOR-HIRE USE

A trooper’s duty is to “protect the lives and safety of the traveling public on state highways” T.C.A. § 4-7-113 (emphasis added). In regulating transportation and for-hire use of the roads, the safety commissioner “has the power to exercise all duties, responsibilities and powers granted the department in title 65, chapter 15, to establish and promulgate rules and regulations necessary for the administration and enforcement of title 65, chapter 15” T.C.A. § 4-3-2012.

Highway patrol officers “have authority to make arrest for any violation of title 65, chapter 15, or of any other traffic law of the state” T.C.A. § 4–7-105. DOSHS Criminal enforcement authority is limited. (1) “unlawful taking of a motor vehicle” T.C.A. § 4-7-114 (2) fraud in registration applications, title 55, chapter 5 and (3) theft of property. T.C.A. § 39-14-103.

EVIDENCE OF PRIVILEGE: BILLS, INVOICES

Statute defines evidence of commerce subject to privilege requirement. “Such enforcement officers, upon reasonable belief that any motor vehicle is being operated in violation of this part, shall be authorized to require the driver thereof to: (A) Stop and exhibit the registration certificate issued for such vehicle; (B) Submit to such enforcement officer for inspection any and all bills of lading, waybills, invoices or other evidences of the character of the lading being transported in such vehicle.”

The trooper under chapter 65 has power to “inspect the contents of such vehicle for the purpose of comparing same with bills of lading, waybills, invoices or other evidence of ownership or of transportation for compensation” and to “impound any books, papers, bills of lading, waybills and invoices which would indicate the transportation service being performed is in violation of this part, subject to the further orders of the court having jurisdiction over the alleged violation.” T.C.A. § 65-15-106 (emphasis added).

DEFENDANTS NOT TRAINED TO ADMINISTER TITLE 55

Such evidences Hamilton County has not trained Messrs. Bennett and Garrett to search for. Defendant county ordains they enforce or administer the motor vehicle laws using criminal authority illicitly.

Bills and invoices, passenger lists, manifests and the like are the requisite evidences of privilege taxable activity for which carrier and motor vehicle titles exist, which law is Mr. Bennett’s pretext for arresting appellant. Defendants are not qualified to administer the police powers applicable to economic regulation. In this typical “traffic stop,” they sought no evidence of privilege to give them standing to sue and to back allegations of wrongdoing.

Since 1905, rules regulate driving privilege

ISSUE — Copies of early law secure meaning of current law, showing legislative/congressional intent and evolution, are not available to the court.

The legislative and regulatory history of Tennessee law, as shown in Appendix exhibits 1–16, confirms that since 1905 the operation of motor vehicles has been treated as a taxable privilege only when exercised for gain or in commerce. These statutes consistently distinguish between public rights of travel and regulated activities requiring licensure. This distinction remains embedded in current law, which continues to define enforcement of such privileges as administrative in nature. Appellant’s arrest bypassed this statutory structure, imposing criminal consequences where the law prescribes notice, hearing, and exhaustion of administrative remedy.

In 1905 the Tennessee general assembly passed S.B. 246 “[t]hat before any owner of any automobile *** used for the purpose of transporting or conveying persons or freight, or for any other purpose *** shall be permitted to operate or permit to be operated any automobile upon any street *** such owner shall register such automobile with the Secretary of State[.]” FN 7

7 https://archive.org/details/actsstatetennes23tenngoog/page/370/mode/2up

An official number” not less than three inches in height” marks the licensee’s automobile front and rear. The law declares “no automobile” shall “be run or driven” in excess of 20 mph, and that anyone controlling a car must slow down when approaching a horse and “make known his approach” by “ringing a bell or sounding a horn.” Sect. 5 of the law says a “willful violation” is a misdemeanor with a fine between $100 and $500 ($1,816 to $9,080 in current dollars) and jail time for “the person, firm or principal agent of any corporation so offending, with full authority for a criminal court jury. FN 8 APPENDIX EX No. 3

8 Figures from bureau of labor statistics “CPI Inflation Calculator,” https://www.bls.gov/data/inflation_calculator.htm?pubDate=20250610

In 1911 a general assembly’s private act let Sullivan County require registration of autos used for any transportation-related purpose. APPENDIX EX No. 4

Very simply, Shannon’s 1917 code lists annual fees “for each automobile or rent or hire” at $10, with “sight-seeing car or truck with capacity of 12 people paying $15. The heading is “Automobiles for hire or rent” Shannon’s Compilation of Tennessee Statutes Vol. 1 p. 436 § 712. Chapter 34 is titled, “Self-propelling public conveyances other than street railways for street transportation are common carriers whose business is regulated as a privilege,” citing 1915 ch. 6 sec. 1. APPENDIX EX No. 5

TURNPIKE NOT, BUT PUBLIC HIGHWAY FREE

Constitutionality of a 1915 private act on privilege for Davidson County “is doubted” for “this tax purports to be a privilege tax imposed upon the mere use of an automobile *** for pleasure. A privilege tax cannot be imposed on anything or any act, unless it constitutes a business, occupation, pursuit, or vocation. Pleasure-taking does not constitute a business, occupation, pursuit, or vocation *** ; and, therefore, is not subject to privilege taxation.”

Can the legislature impose a privilege tax upon the mere taking of pleasure by the people, which is the exercise of an inalienable right, so long as it does not interfere with the rights of others? The taking of pleasure is of great benefit to humanity, and often a powerful agency for the restoration of health, as well as for the preservation of health.

Shannon’s Vol. 1 p. 438 § 712

The state supreme court, however, turned this argument aside as to turnpikes but not as to public roads. “[T]he legislature may declare it to be a privilege to operate pleasure cars over the turnpike road of our counties. Such operation amounts indeed to the pursuit of an occupation with many, though not for gain” Ogilvie v. Hailey, 141 Tenn. 392 (1919). Pleasure use on a turnpike is commerce because the traveler must pay a business to cross onto the road. APPENDIX EX No. 5

“This idea of a turnpike arrived with the early settlers from England where toll gates were constructed with long spears or pikes directed toward the vehicles. When the toll was paid, the gate turned parallel to the road allowing the vehicle or animal to pass. From this device came the name ‘turnpike’ which, almost immediately, became to mean a road on which tollgate or turnpikes were erected” (History p. 9). FN 9

9 History of the Tennessee Highway Department (Nashville: 1959) compiled by the Tennessee state highway department, highway planning survey division in cooperation with the U.S. department of commerce, bureau of public roads

REGISTRATION ALWAYS ON ‘OPERATION’

Shannon’s 1917 record in Vol. II, chapter 33, at 307a186, p. 2151, covers ‘Registration of automobiles and the regulation of their operation.” It begins, “Before the owner of any automobile, motorcycle, auto truck, traction engine, or other vehicle of like character, used for the purpose of conveying persons or freight or for any other purpose *** shall operate or permit to be operated upon any street, road, highway, or other public thoroughfare, or elsewhere in Tennessee, such owner shall register such vehicle with the secretary of state” giving details of horsepower, make, owner ID and pay fees on a sliding scale based on “passenger seating capacity” (emphasis added).

The statutory construction rule of reading in law ejusdem generis requires the phrase “for any other purpose” be seen as constrained by the narrow context already set in the law, referring to other for-hire use, not pleasure, or “taking of pleasure” auto use. APPENDIX EX. No. 6. Chapter 24 in 1917 Shannon’s code deals with any person or business “operating for hire any public conveyance *** affording a means of street transportation” similar to that of a railway, but not on fixed tracks. Such business is under bond, permit and/or license. The 1918 code shows tax rates for autos for hire or rent. APPENDIX EX. No. 7

FIRST AUTO, NOW VEHICLE IN FOR-HIRE USE

In the 1918 Shannon’s code, sold for-hire automobiles “receive a transfer certificate” from the secretary of state, and the buyer “shall “register such certificate with the court clerk of the county” and pay 50 cent fee. An early indictment under the penalty provision at 3079a193 (p. 2153) was for a motorcycle “operated” (“used for the purpose of conveying persons or freight”) without having been registered. Metal plates are detailed at 3079a188. The owner or operator “of a motor vehicle” files annually a report to the secretary of state and pays fees based on vehicle “passenger seating capacity” (1914, ch.8, sec. 5). 3079a190. Auto dealers are regulated and must notify the state “of said sale, giving the name of purchaser, make and horsepower of the machine.”

Presumptive authority over noncommercial users appears to arise out of safety concerns for horses on the road and the 20 mph for all users. “No automobile shall be run or driven *** at a rate of speed in excess of twenty milers per hour.” A “person driving such automobile” shall stop the car until the horse passes. 3079a196. APPENDIX EX. No. 8

Toll roads were unpopular. Most went bankrupt (History p. 13). Public roads, for which the people clamored, are useable at liberty by all per right. Regulation and taxation from the beginning applied to business or commerce in which the private living or gain is on the road.

The general assembly (“GA”) passed for Hamilton County a single private act relating to motor vehicles, according to County Technical Assistance Service run by University of Tennessee. The 1921 private acts chapt. 566 requires “all owners or operators of ‘for hire’ vehicles propelled by steam, gasoline or electric power and used for the purpose of conveying passengers, goods, wares or merchandise, shall cause to have painted on both sides of their vehicle or vehicles offered for public hire, in letters not less than one and one-half inches (1½) inches [sic] high, in such manner as to be plainly visible, the name or monogram or trade mark of the individual, firm, corporation or association owning or operating such vehicle or vehicles.” (sect. 1). Further, “it shall be unlawful for any vehicle propelled by steam, gasoline or electric power to carry for public hire any passengers, goods, wares or merchandise unless such owner or operator shall first give bond or security as hereinafter conditioned and specified” (sect. 2). Local police and deputies enforced the law. FN 10 APPENDIX EX. No. 9

10 https://www.ctas.tennessee.edu/node/102710/printable/pdf

The GA in 1925 passed the Hamilton County private act chap. 729 for taxi cabs, “hereby declared to be common carriers” and liable in sect. 3 to carry bond or insurance. The activity regulated is “operating” a “motor vehicle” in either freight or passenger service. FN 11 APPENDIX EX. No. 10

11 https://www.ctas.tennessee.edu/node/97477/printable/pdf

COMMERCE USERS TAXED TO PAY ROADS

Commerce in Tennessee history pays fees and taxes for road upkeep. Gov. Andrew Johnson’s maxim in 1853 on highway finance was “He who derives the greatest benefit shall pay correspondingly for the benefits received” (History p. 34). A law “requiring all persons, firms, associations, joint stock companies, syndicates and corporations engaged in or carrying on the business” of selling fuel had to pay a privilege tax of 2 cents per gallon “used solely in the construction and maintenance of a highway system in the state.” In 1918 the cost of wagon hauling per ton mile for wheat was 30 cents, but 15 cents on hard surface road by truck in public benefit (History p. 34).

CARRIERS TAXED AS UTILITIES

Trucking, hauling and transportation are regulated as utilities. In 1932 the code, Vol. 1, shows privilege operations generally in Article VI, requires registration of vehicles used for “conveying persons or freight” at § 1149. APPENDIX EX. No. 11.

The 1932 code, Vol. 2, on utilities, duties as to railroad passengers in art. 3, tickets, separating blacks in art. 5, and whites, jitneys “operating for hire” as “public conveyance” under privilege in art. 6. It follows with privilege regulation of barbers, embalmers and plumbers. APPENDIX EX. No. 12 The 1934 Annotated Code of Tennessee, Vol. 4, Article IA “motor carriers” shows large scale supervision of motor vehicles use in fleets. APPENDIX EX. No. 13

The highway patrol (Acts 1929 (E.S.) ch.25, § 1), department of safety (Acts 1937, ch. 33) and the UAPA (Acts 1974, ch. 725) centralized state control over the transportation privilege.

THROWN OPEN FOR PUBLIC TRAVEL OR USE FREE OF CHARGE

“That a highway declared to be public by statute is used chiefly by a private individual does not make it a private highway, where the whole public has the right to use it.” Bashor v. Bowman, 133 Tenn. 269, 180 S.W. 326, 1915 Tenn. LEXIS 92 (1915) (Westlaw headnote). “We are of opinion that there is no ambiguity about the ordinary meaning of the expression ‘public highway.’ We think there can be no doubt that the common understanding of a public highway is such a passageway as any and all members of the public have an absolute right to use as distinguished from a permissive privilege of using same” Standard Life Ins. Co. v. Hughes, 203 Tenn. 636, 642, 315 S.W.2d 239, 1958 Tenn. LEXIS 229 (1958). (Doc. 1, PageID # 73, administrative notice)

“A regulated monopoly in the motor carrier field is not authorized by Chapter 119, Public Acts 1933. The highways of the State belong to the people of the State. Many of these highways have been improved at large cost to the taxpayers. It is the convenience and necessity of the people of the State that must be given predominant consideration by the Commission, and not that of contending motor carriers operating free over these highways. It is within the power of the Commission, in proper cases, to permit several motor carriers to operate over the same route. No one carrier, by virtue of a certificate, obtains a monopoly over the route granted.” Dunlap v. Dixie Greyhound Lines, 178 Tenn. 532, 160 S.W.2d 413, 418 (1942) (emphasis added). “All roads, streets, alleys, and promenades where legally dedicated and thrown open for public travel or use free of charge shall be exempt from taxation” Tenn. Code Ann. § 67-5-204 (emphasis added).

REGULATIONS AT LIMIT ADMIT FREEDOMS

State law recognizes ingress-egress rights of the general public to use the public right of way apart from privilege, as noted in the exceptions law on registration. “(a) Every motor vehicle or motorized bicycle, as defined in chapter 8 of this title, and every trailer, semitrailer, and pole trailer, when driven or moved upon a highway, and every mobile home or house trailer, when occupied, shall be subject to the registration and certificate of title provisions of chapters 1-6 of this title, except: (1) Vehicles driven or moved upon a highway in conformance with chapters 1-6 of this title relating to manufacturers, transporters, dealers, lienholders, or nonresidents; (2) Vehicles that are driven or moved upon a highway only for the purpose of crossing the highway from one (1) property to another; (3) Any implement of husbandry; (4) Any special mobile equipment” or vehicle owned by the U.S. government or in a foreign state. T.C.A. § 55-3-101 (emphasis added) FN 12

12 Farm tractor or combine crossing a road from one field to another is exempted in (3) as “implement of husbandry.” Exception (2) refers to movement by right upon the way thrown open to the public by those T.C.A. 4-7-113 refers to as “the traveling public.” See appellant administrative notice on ingress-egress rights connected with his rights to abode and land. Doc. 29 PageID # 306. “Since 1905 under the holding in Frazier v. East Tennessee Tel. Co., 115 Tenn. 416, 90 S.W. 620, 3 L.R.A.,N.S., 323, Tennessee has been committed to the view that the use of public rights-of-way by utilities for locating their facilities is a proper highway use subject to their principal purpose as travel and transportation of persons and property.” Pack v. Southern Bell Tel. & Tel. Co., 19 McCanless 503, 511 (1965). Note reference to “The traveling public using said highways” Dunlap v. Dixie Greyhound Lines, 14 Beeler 532, 416(1942)

EVERY DRIVER LICENSE COMMERCIAL

The driving privilege formerly was under the “uniform motor vehicle operators’ and chauffeurs’ licenses law” (Acts. 1937, ch. 90, § 1) in title 50, was amended as become the “uniform classified and commercial driver license act of 1988” under the administration of the U.S. department of transportation (“administrator” defined, § 55-50-102). According to the familiar conjunctive/disjunctive canon in the rules of statutory construction (see Reading Law The Interpretation of Legal Texts by Antonin Scalia & Bryan A. Garner, 2012), the word “and” indicates a driver license is classified AND commercial. Appellant, whose occupation is radio journalist, has a second occupation. This one under privilege with a driver license, that being “driver and operator of a motor vehicle,” with a Class D driver license up to 13 tons motor vehicle weight.