I am suing in chancery court, insisting I have right to sue two commissioners for fraud, though only one — revenue — has affected a direct injury to my rights. I am suing Long for participating in enforcing a fraudulent reading of sect. 139 in the financial responsibility law, and having troopers at the ready to arrest me traveling in my revoked minivan. (Photo David Tulis)

CHATTANOOGA, Tenn., Friday, April 25, 2025 — Our love labor for Christian liberty and constitutional government is rooted in childlike trust in written revelation. We fight in court to end oppression because we read the Word of God as authoritative in our personal lives and upon the public weal. We read state law as limiting what commissioners, judges and governors do.

I read the epidemic statute with such simple heart that on Oct.2, 2020, I sue Gov. Bill Lee for fraud and fight 878 days in court to save lives, albeit his program kills at minimum 150,000 Tennesseans who take the jab.

I read the financial responsibility law (TFRL) with the same simplicity and integrity. The TFRL doesn’t require auto insurance of all drivers, operators, registrants or travelers. It requires insurance of people adjudicated as high risk by a court. These people have to have “evidence” or “proof” of financial responsibility while using the roads on a conditional privilege.

This woman is among tens of thousands illegally prosecuted for “driving without insurance.” (Photo from Chattanoogan.com)

They exercise the “driving” privilege on condition. The condition is: You must have insurance, a special insurance. It comes with a certificate. That certificate is your proof. You must keep the special “motor vehicle liability policy,” and department of safety will let you keep your license.

Let’s get to the basics of “reading the Bible” and “reading law.” Maybe caring about men’s laws and how they are obeyed migh help make us better Christians.

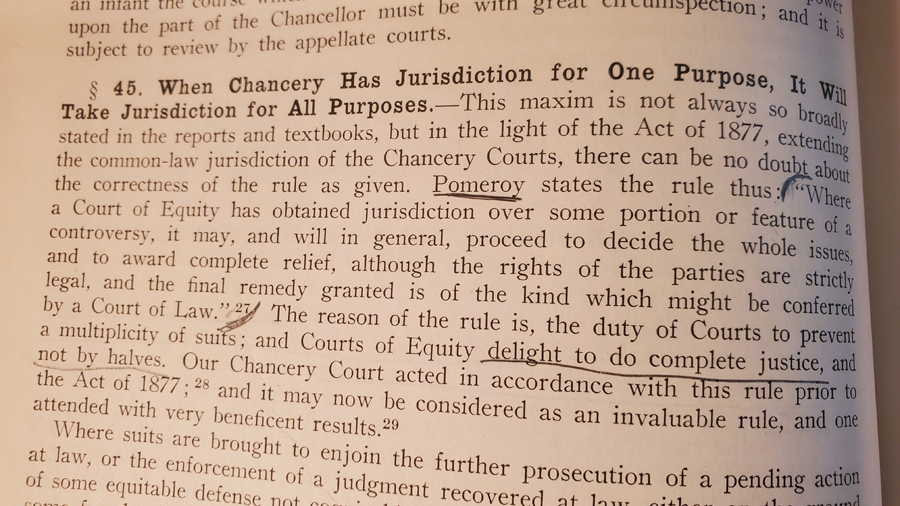

‘Construe statutes as we find them’

Our construction of a statute is more likely to conform with the General Assembly’s purpose if we approach the statute presuming that the General Assembly chose its words purposely and deliberately, Tidwell v. Servomation-Willoughby Co., 483 S.W.2d 98, 100 (Tenn.1972); Merrimack Mut. Fire Ins. Co. v. Batts, 59 S.W.3d 142, 151 (Tenn.Ct.App.2001), and that the words chosen by the General Assembly convey the meaning the General Assembly intended them to convey, Limbaugh v. Coffee Med. Ctr., 59 S.W.3d at 83; BellSouth Telecomms., Inc. v. Greer, 972 S.W.2d 663, 673 (Tenn.Ct.App.1997). Thus, we must construe statutes as we find them, Jackson v. Jackson, 186 Tenn. 337, 342, 210 S.W.2d 332, 334 (1948); Pacific Eastern Corp. v. Gulf Life Holding Co., 902 S.W.2d 946, 954 (Tenn.Ct.App.1995), and our search for a statute’s purpose must begin with the words of the statute itself, Blankenship v. Estate of Bain, 5 S.W.3d 647, 651 (Tenn.1999); State ex rel. Comm’r of Transp. v. Medicine Bird Black Bear White Eagle, 63 S.W.3d 734, 754 (Tenn.Ct.App.2001).

‘Interpret them as written’

We must give a statute’s words their natural and ordinary meaning unless the context in which they are used requires otherwise. Frazier v. East Tenn. Baptist Hosp., Inc., 55 S.W.3d at 928; Mooney v. Sneed, 30 S.W.3d 304, 306 (Tenn.2000); State v. Fitz, 19 S.W.3d 213, 216 (Tenn.2000). Because words are known by the company they keep, State ex rel. Comm’r of Transp. v. Medicine Bird Black Bear White Eagle, 63 S.W.3d at 754, we should construe the words in a statute in the context of the entire statute and in light of the statute’s general purpose, State v. Flemming, 19 S.W.3d 195, 197 (Tenn.2000); Lyons v. Rasar, 872 S.W.2d 895, 897 (Tenn.1994); Wachovia Bank of N.C., N.A. v. Johnson, 26 S.W.3d 621, 624 (Tenn.Ct.App.2000).

‘Cautious about consulting legislative history’

We must be cautious about consulting legislative history. BellSouth Telecomms., Inc. v. Greer, 972 S.W.2d at 673. A statute’s meaning must be grounded in its text. Thus, comments made during the General Assembly’s debates cannot provide a basis for a construction that is not rooted in the statute’s text. D. Canale & Co. v. Celauro, 765 S.W.2d 736, 738 (Tenn.1989); Townes v. Sunbeam Oster Co., 50 S.W.3d 446, 453 n. 6 (Tenn.Ct.App.2001). When a statute’s text and the comments made during a legislative debate diverge, the text controls. BellSouth Telecomms., Inc. v. Greer, 972 S.W.2d at 674.

The fighting and mercy reporter at GiveSendGo

David runs a personal nonprofit fighting and mercy ministry. He thanks you for checks sent directly to c/o 10520 Brickhill Lane, Soddy-Daisy, TN 37379. Also at GiveSendGo.

I am reporter with Eagle Radio Network — marvelously playing rock hits in Chattanooga, and online at https://www.eagleradionetwork.com/