Officials in Tennessee are rejecting clear limits in state law, leading to ruin of livelihoods among tens of thousands of people in Chattanooga local economy and beyond.

By David Tulis / NoogaRadio 92.7 FM

The quarantine law specifically requires care not to damage commerce and travel, yet panicked officials are shutting down businesses with no proven connection to sickness and forcing rolling defaults across the landscape as people are unable to pay bills. The emergency law gives no authority to shut down businesses in areas where there is no known connection to a virus or sickness.

The most recent order in Chattanooga, EO 2020-04, shutters businesses that require close contact between customer and provider, as explained by police chief David Roddy.

East Ridge is apparently the first municipal corporation, led by Mayor Brian Williams, to order closed all “nonessential” businesses.

Officials in Southeast Tennessee are being stampeded by dictatorial executive fiat of mayors and governors elsewhere.

With thousands thrown out of work by official action, many people are applying for jobless benefits. This week unemployment offices were stampeded by 20x the normal number of petitioners.

One exception to panicky overreaction is Grundy County mayor, Michael Brady, who acts in a limited fashion only upon those whom he has legal authority over — namely, people on the county payroll. He closes county buildings. His edict merely “urge[s] all citizens” to do their part in health and safety measures. He deems no one’s calling or occupation “non-essential.”

Another commendable exception is Gov. Bill Lee, who insists on respecting the people of Tennessee and giving them leeway to decide how far to pare back business operations in view of the accepted social distancing rules.

Emergency powers are meant to preserve life and preserve the dignity and prosperity of people and not ruin them.

The general assembly says the state is “vulnerable to a wide range of emergencies, including natural, technological, terrorist acts, and manmade disasters” and that they “threaten the life, health, and safety of its people; damage and destroy property; disrupt services and everyday business and recreational activities; and impede economic growth and development.” The vulnerability is “exacerbated by the growth in the state’s population, in the elderly population, in the number of seasonal vacationers, and in the number of persons with special needs.” Tenn. Code Ann. § 58-2-102. Legislative intent.

The problem is that state action outside of its authority bringing injury to services, business, economic growth, the elderly and those people “with special needs.”

The shutting down of thousands of categories of business goes beyond the legislature’s intent to preserve and to spare. “It is the intent of the general assembly to reduce the vulnerability of the people and property of this state; to prepare for efficient evacuation or shelter-in-place of threatened or affected persons ***.” In practice, it appears that everyone is “threatened or affected,” so no limit is required as to the scope of exercise of police power upon the public.

Time limit ignored

Local officials also are allowed to develop emergency departments and plans “safeguarding the life and property” of the citizens. Tenn. Code Ann. § 58-2-110. Their local emergencies are limited to seven days, but can be renewed.

In East Ridge, the emergency orders to not give a self-expiring seven-day deadline. Mayor Andy Berke of Chattanooga, in his EO 2020-3, says it “shall remain in effect until this order is withdrawn.” A second order also uses similar language.

The reasonable fear among many of the state’s 6.5 million people is that controls put in place temporarily will not “sunset” into oblivion if state or local officials find them useful in securing the public interest or maintaining “health, safety and welfare” of the public.

Local governments routinely violate constitutional rights, and in the Flu 19 epidemic, are showing themselves consistent. Law enforcement agencies routinely violate Tenn. Coce Ann. Title 55, motor and other vehicles, but imposing the state trucking, shipping, hauling, moving, transportation law on people who are private and pleasure users of the road in travel, not involved in trucking, shipping, hauling, moving, transportation. Sheriff Jim Hammond and Mayor Andy Berke’s police chief David Rodd also operate a system of general arrest warrants, which are forbidden by law, specifically Tenn. Code Ann. § 40-7-109, grounds for arrest by officer without a warrant.

Quarantine law aims inward, not outward

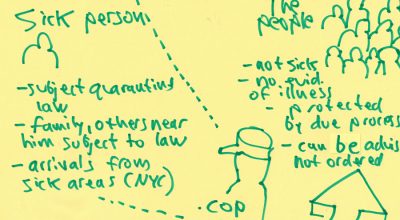

The state quarantine law is not directed at businesses and private gatherings of people not known to be sick. It is directed against ill or suspected ill people. The law scrupulously avoids the panic in evidence today of suspecting everybody to be ill or infected.

Black’s Law Dictionary defines quarantine as a “period of time (theoretically forty days) during which a vessel, coming from a place where a contagious or infectious disease is prevalent, is detained by authority in the harbor of her port of destination, or at a station near it, without being permitted to land or to discharge her crew or passengers. Quarantine is said to have been first established at Venice in 1484.”

“Whenever yellow fever, cholera, smallpox or other epidemic diseases appear in any locality within the state, and information thereof is brought to the knowledge of the department, the commissioner shall prepare and carry into effect such rules and regulations as, in the commissioner’s judgment, will, with the least inconvenience to commerce and travel, prevent the spread of the disease.” This provision appears twice in the same provision.

The 1879 law lets the state commissioner of health “erect necessary temporary buildings for the disinfection of passengers, baggage, cargo and other matter believed to convey the contagious principle of cholera, yellow fever, smallpox and other epidemic diseases.” Tenn. Code Ann. § 68-1-202. Violating a quarantine is a misdemeanor.

Due process required

The state’s tuberculosis quarantine law gives details how due process is to operate in time of contagion. The rule is this: a doctor’s finding is the first step in due process; a judge’s finding the second if there is a dispute over who is subject to quarantine.

Tuberculosis has long been a scourge on humanity, and the quarantine law lays out how the state and its public servants are to protect the public. It is via due process, because a quarantine is a kind of sanctioned kidnapping. The patient is coerced into a location against his will because he is sick and contagious, and is bound to stay in a “detention facility” — a camp, building or hospital. Tenn. Code Ann. § 68-9-202.

A suspected carrier is under arrest and the stae agent allowed “to make or have examinations made by a duly licensed and practicing physician of this state to be selected by the health officer, of persons reasonably suspected because of known clinical or epidemiological evidence of having infectious tuberculosis.”

The state’s “officers are directed and empowered to isolate or quarantine persons who, because of known clinical or epidemiological evidence, are suspected of having infectious tuberculosis.” The patient can be released only when a doctor decides he no longer can infect anyone. Tenn. Code Ann. § 68-9-204. Quarantine — Commencement — Termination — Standards.

The most valuable lesson from this law is that due process rights must be respected. A lengthy provision describes how the state must prove with legal evidence that a person is sick, and the judge orders him to be confined if evidence is sufficient. Tenn. Code Ann. § 68-9-206. Incarceration of suspect — Procedure — Appeal — Violation of quarantine.

Other provisions of law do not repeat this protocol. But they don’t need to. The constitution guarantees due process rights in the bill of rights, which protect every individual from state action without proper charging instruments, proof and right to trial by judge and jury.

The constitutional rights in Tennessee are secure, even in times of illness.

Governor’s huge powers

The statute gives the governor power to make edicts that “have the force and effect of law.” Tenn. Code Ann. § 58-2-107 A state of emergency can last no more than 60 days “unless renewed by the governor.” He is required to declare whether the emergency is “due to a minor, major, or catastrophic disaster.”

He is allowed to cut red tape, control agencies and people, “Direct and compel the evacuation of all or part of the population from any stricken or threatened area within the state if the governor deems this action necessary for the preservation of life or other emergency mitigation, response, or recovery,” control movements or occupancy of threatened areas, suspend alcohol sales, control temporary housing, redirect utilities, limit liabilities of healthcare workers except for any “act or omission was the result of gross negligence or willful misconduct.”

In the enumerated powers of Gov. Lee, the law twice makes clear that he does not have authority to “commandeer or utilize” a citizen’s firearms or ammunition, in strict regard to the bill of rights. Nor does he have authority to mess with the press.